St Catherine’s Well, Killybegs, County Donegal

The rain was coming down hard in Killybegs when we found the well. I was on a camping holiday with my son, but the trip so far had been a washout. A lot of card games had been played in the camper van, and there had been a bit of football on empty beaches under weeping skies. It had still been fun, in a wet kind of a way, but we were both looking forward to the promised end of the downpour. In the meantime, I had heard there was a well in town, and my son had resigned himself to his father’s eccentric pursuits being enfolded into his holiday.

The map said that the well was to be found near the harbour, and so it was, but it was not the kind of harbour I was expecting. Killybegs is Ireland’s biggest fishing port, and as well as big industrial trawlers, it is home now to container ships and other such hub operations of the global economy. We pulled into the giant asphalt car park which, according to the map, was only a few yards from the well, and this is what we saw:

These are blades for giant offshore wind turbines. The scale is quite astonishing up close. Turn around 180 degrees though, and you will see a different sight. A footpath winding up a green hill towards the stump of a ruined castle, and, at the end of the path, this:

This is St Catherine’s well. It’s too concretey for my tastes, but maybe this is appropriate for a well in an industrial area. The setup features an encased statue of the saint at its heart, looking down on the waters, which, when we were there, were shimmering and shivering with the giant raindrops that fell in them incessantly.

Who is St Catherine? The stone wheel at the bottom of her statue is the clue. This is St Catherine of Alexandria, a fourth-century martyr revered throughout North Africa and the Middle East, and who was popular in medieval Europe. Catherine’s story is positively novelistic. She was said to be a beautiful young Egyptian Christian who publicly objected to the Roman Emperor Maxentius about the worship of idols. The Emperor sent a team of fifty philosophers to debate the issue with her, but unfortunately for him Catherine had brains as well as beauty, and she demolished them all.

After putting the philosophers to death for their failure, Maxentius decided that Catherine was Empress material, and offered to marry her. She refused either to marry him or to recant her faith, so Maxentius demonstrated his love for her by having her beaten and then tortured on a spiked wheel. When the ‘Catherine Wheel’ splintered into pieces without harming her, many in the audience, including the Emperor’s current wife and many of his soldiers, converted to Christianity. Maxentius had them all beheaded, and then beheaded Catherine too. It is said that milk, rather than blood, flowed from her neck.

After her martyrdom, Catherine’s body was carried to Mount Sinai where her relics became the focus of the desert Monastery of St Catherine of Sinai - the oldest continually-occupied monastery in the entire Christian world, and one that I would dearly love to visit before I die.

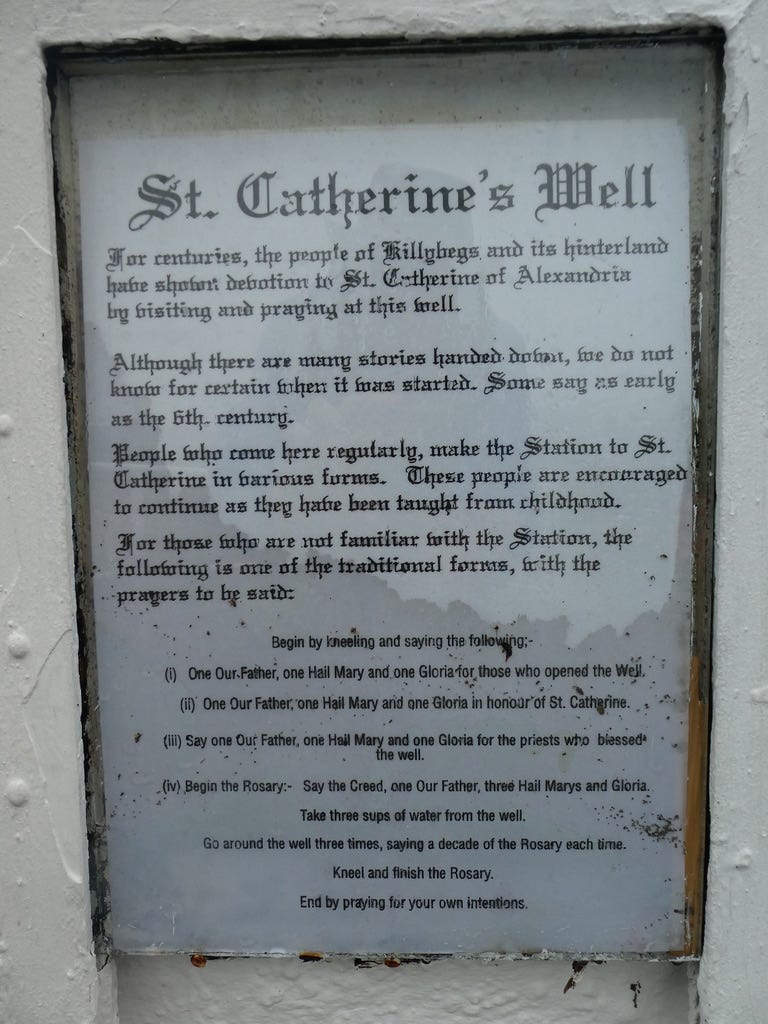

Like I say, it’s quite a story. But what does it have to do with Killybegs? It’s an intriguing question. Most Irish wells, though not all, seem to be dedicated to Irish saints. Patrick and Brigid are the most popular nationwide, I would guess, while many other more localised saints are the patrons of local wells. So what is this Egyptian saint doing here? According to the signboard by the well, she has been venerated in this small Donegal town for a long time - possibly since the sixth century:

There is an intriguing story which explains the saint’s cult here. The tale goes that a boatload of Egyptian Coptic monks were caught in a storm out at sea and prayed to St Catherine for rescue. Washed safely to shore, they dedicated this spring to her memory and blessed it in her name. The well has been venerated here ever since.

But what would Egpytian Coptic monks be doing in a boat off the coast of Donegal? According to one school of thought, the answer is: Christianising Ireland.

Although St Patrick is known worldwide as the ‘Apostle to Ireland’, there were Christians here before him, as he acknowledged himself in his writings. Furthermore, Patrick did his work in the north and west of the country. Elsewhere, there is growing evidence for the presence of Egyptian Coptic Christians in the country before him. Their presence has been cited to explain specifically Irish curiosities like early Christian handbells (those found here look similar to those from Egypt), monastic round towers (which look somewhat like Coptic bell towers), the binding of certain gospel books, and even Irish place names. ‘Kil’, for example (as in Killybegs) could be a corruption of ‘cell’, while names like Dysert - a strange place name which pops up all over the country - may be a corruption of ‘desert.’

My favourite historical mystery here is the case of the Irish high crosses. These monuments were raised across the country to teach an illiterate population the Christian story. Usually they would feature the crucifixion, scenes from the gospels and one or two important saints. They look like this:

Sixty of these crosses remain intact. How often does St Patrick appear on any of them? As far as I know, not once. The two most popular saints on the crosses, by an overwhelming margin, are two Egyptians: St Anthony the Great and St Paul of Thebes.

The notion that Irish Christianity originated in the Egyptian desert, rather than in Rome or Constantinople (for more on this theory, I recommend this lecture by Irish researcher Alf Monaghan) is significant for a lot of reasons. If it is true, it means that the original Christian stream here in northwestern Europe (including neighbouring Britain, which was first Christianised by Irish monks) was the Christianity of the Desert Fathers. If that much blurbed ‘Celtic Christianity’ was a faith of the wilderness rather than the city, of monks rather than bishops, of the hermit’s hut rather than the urban church, then our original practices in these islands start to look quite different, and that might say something about what we should be returning to. You probably know me well enough to know how much I like this idea.

Is this how St Catherine of Alexandria ended up in rainy Donegal? We can’t know, of course. But I like to think so. Ireland’s green desert makes more sense to me when I hear stories like this. So does my own Christian journey.

"the desert Monastery of St Catherine of Sinai - the oldest continually-occupied monastery in the entire Christian world"

That's where my avatar image originates from, a religious icon called Christ Pantocrator (which is an awesome word to begin with).

Though not religious, I was really impressed by it when I saw it the first time. The style looks so fresh, though it is one of the oldest Byzantine religious icons, dating from the 6th century AD, and to me icons usually look kind of 'stiff', for lack of a better word.

But what really impressed me, was this (quote from Wikipedia):

"Many agree that the icon represents the dual nature of Christ, illustrating traits of both man and God, perhaps influenced by the aftermath of the ecumenical councils of the previous century at Ephesus and Chalcedon. Christ's features on his right side (the viewer's left) are supposed to represent the qualities of his human nature, while his left side (the viewer's right) represents his divinity. His right hand is shown opening outward, signifying his gift of blessing, while the left hand and arm are clutching a thick Gospel book."

If you click my avatar (or go to Wikipedia), you may see the composite image I've made with the original in the centre, and the two mirrored halves of the face at either side. I need to get that framed, so I can look at it more often.

I registered on Substack because of Paul's writing years ago, and chose to use the composite image of the Sinai Christ Pantocrator icon as an avatar, not knowing about Paul's conversion at the time. It's one of these nice little religious coincidences that happen to me from time to time, making me wonder whether it's a sign from above that I should shape my agnosticism into something more focussed.

Maybe I need to visit the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine of the Holy and God-Trodden Mount Sinai as well.

I just loved reading this! Thank you for fresh information ( never knew about the Coptic monks). The well isn’t terribly romantic, is it? Those bars look positively playground material (circa 1960’s). But as you wrote, fitting for its industrial location.