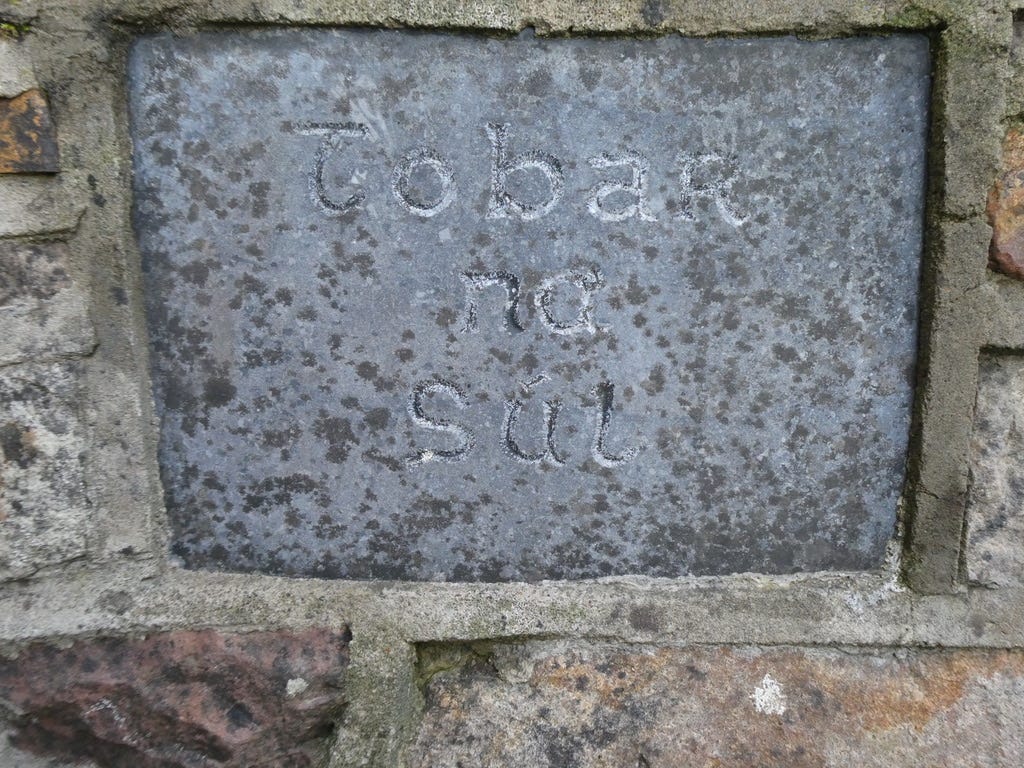

Tobar Na Sul, Bridgetown, County Clare

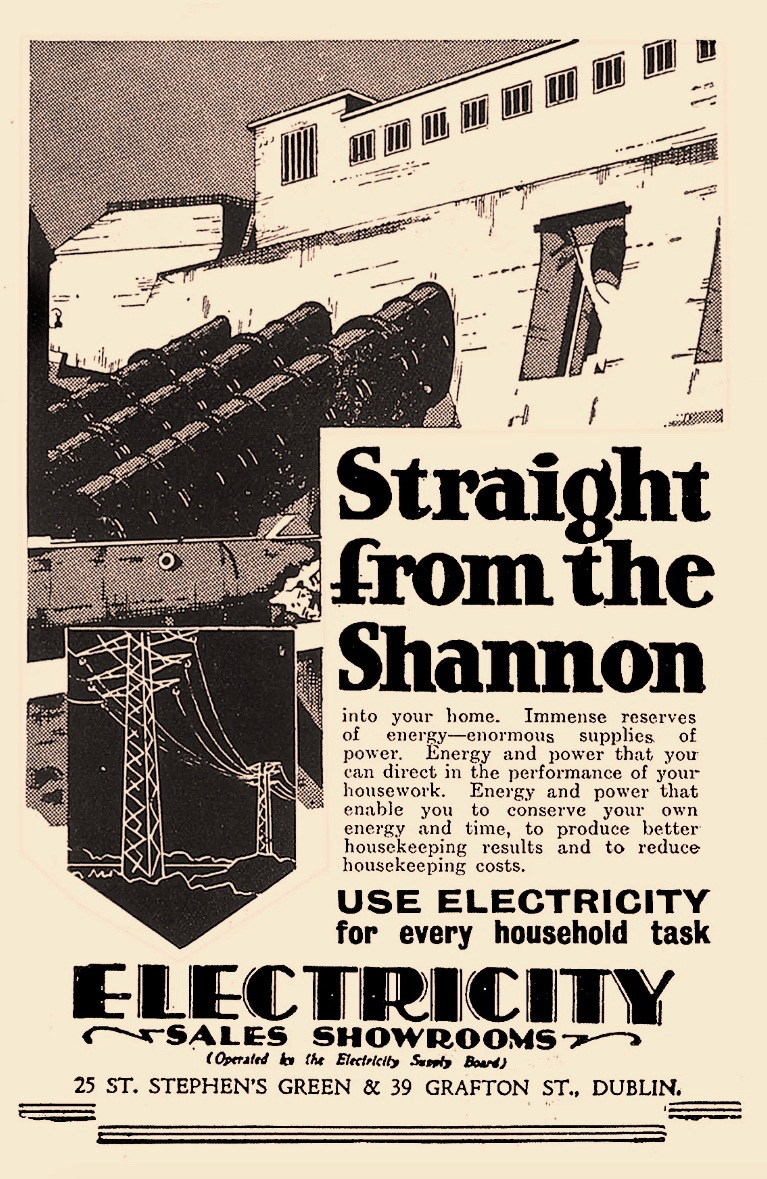

Not much happens in Bridgetown, County Clare - but you’re getting used to opening sentences like that, aren’t you? This time around, there is not even any exciting Ecclesiastical history to report, as there was last week. Bridgetown - which is not a town, and only just qualifies as a village - is a small settlement not far away from O’Brien’s Bridge in County Clare, a lovely sixteenth century stone bridge across the Shannon. It is a little way downstream from the Parteen Weir at the southern foot of Lough Derg, and a little way upstream from the toadlike Ardnacrusha power station, which together have harvested the Shannon for energy since the 1920s.

Ardnacrusha was a revolutionary piece of technology in its time, enabling the newly-independent Irish state to provide huge amounts of electricity for a nation for which it was still a rarity (you can see fascinating photos and accounts of its construction here and here.) But the march of the Machine has consequences. In this case, those consequences included a 90% collapse in the salmon population of the Shannon, which previously had been world-famous for its salmon runs, along with the mass death of trout and eels, the silting up of parts of the waterway, an increase in flooding and the raising of the water level of Lough Derg.

Still at least Ireland now has a carbon-free electricity supply, right? Well, no. When it was built, Ardnacrusha was the biggest hydroelectric scheme in the world, until it was beaten to that title by America’s Hoover Dam. On completion, it produced enough power to meet the electricity demand of the whole of Ireland. Today it produces just 2% of it. That’s how much the thirst for electricity has increased in one short century. An astonishing seventy per cent of all that electricity will be swallowed by Internet server farms by the end of this decade.

Behold! Sustainability!

It’s in this context that, on arriving in Bridgetown, I found the well I was searching for overshadowed by a giant protest sign:

The giant wind turbines - subject to similar local protests across the land - are the latest Big Tech solution to the power ‘needs’ of the country: ‘needs’ which have accelerated a thousandfold in a century, and will continue to do so. Everybody wants insta-access to the shiny flicky pictures on the little Satanic Rectangle in their back pockets, but nobody wants to live in the middle of the power station needed to supply it. Well, get used to it, people, because the whole landscape will be a power station soon. Then there’ll be nowhere to hide except inside your VR headsets. Got a problem with that? Then take a hammer to your phone!

Sorry. I’m supposed to be writing about wells.

Ahem. Here is this week’s offering:

Tobar na Súil literally means ‘the well of the eyes’, and it’s a common well name across the land, perhaps even the most common. ‘Eye wells’ seem to be the most common type of healing well. In her book The Holy Wells of County Cork (recommended; it has some beautiful pictures too), and in her accompanying blog, my fellow well-nerd Amanda Clarke notes that, of the 330 wells she visited in Cork, 71 were eye wells; that is, wells noted for being able to cure eye diseases through prayer and bathing the eyes. That’s just over 20%. I can’t find any figures for the country as a whole (there probably aren’t any) but if it were more or less the same, that would mean there were about 600 eye wells in Ireland. It has been suggested that peat fires in smoky, badly-ventilated cottages may have caused many of the eye problems for which cures were sought at these wells.

You would have trouble bathing your eyes in Bridgetown’s Tobar Na Sul now though:

Yes, it’s dry. And yet somehow, it’s still subject to an officious little warning about the consequences of drinking water that isn’t available to drink anyway:

Interestingly, though, Amanda Clarke points in her research to a notion I hadn’t come across before: a possible alternative definition of the phrase ‘eye well.’ Instead of simply being a place which could effect physical cures for diseased eyes, she says, eye wells might be places of spiritual healing also. You’ll have heard the phrase ‘third eye’, I’m sure. Doubtless you’ll have heard, also, the notion that certain people have ‘the sight’ - an ability to experience spiritual realities most of us aren’t aware of. Certainly in Ireland, and England come to that, the old biddies who lived down the lane and had ‘the sight’ were to be treated with extreme caution.

Clarke quotes authors Walter J Brenneman & Mary G Brenneman on the subject:

There is, most probably, a deeper meaning to the healing of eyes. For example, Irish mythological tradition associates the eyes with wisdom, in the sense of “seeing” into the meaning of things. We speak of a “seer” as one who has prophetic wisdom. In a sense, wisdom as healing of the eyes occurs when those elements that are separated due to illness or injury are brought together again, that is, they are made whole, healed. When the eyes are made whole, they are able to see into the meaning of things again.

Well, maybe. Who knows? I like the notion, but I can’t prove it. But then I’ve not looked into it deeply enough. Speaking of looking deeply: if you look more closely at the landscape about Tobar Na Sul you will get a pleasant surprise. The well itself, which is a spring appearing from a brambly hillside in a field, is in fact still flowing. For some reason, it no longer comes out of that pipe by the road - but you can see the water flowing quietly beneath the briars and the bracken. Can you spot it?

That’s how it is everywhere. The small things quietly do their work while the humans built temples to money and speed and noise all around them. Then, one day, those temples all fall down again, but the water keeps flowing. Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!

I do like waking up on a Sunday morning and hurrying to my laptop for the latest instalment of these well stories. They always transport me to another slower, quieter, deeper and more real and satisfying world. The thought that we are carpeting the countryside with wind turbines and solar panels, just to power our phones is appalling though.

The part about the well doing its thing quietly reminded me of a homily I heard about God’s work being like a tree. God works quietly, slowly, at his own pace, and you think nothing is happening, but then there it is - like a fully grown tree.