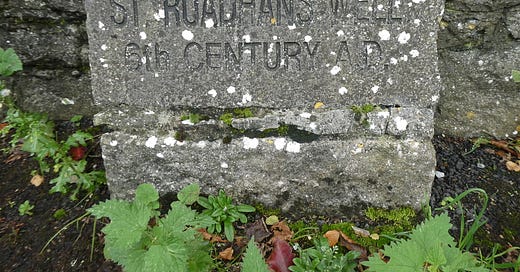

St Ruadhan’s Well, Lorrha, County Tipperary

After forty-three recorded visits to the holy wells of Ireland I struggle to avoid repeating myself. The wells themselves are almost always unique; quite unlike each other in look and feel. Still, I’ve noticed that many of the places they are set in have a similar history, which could be summed up in the phrase, ‘this tiny, quite village was once a major ecclesiastical site …’ Or something like that. You could probably use that phrase for thousands of places around the country, such is the richness of the early Christian history here.

So, here we go again. This time we’re in the (small and quiet) village of Lorrha, on the green plains of Tipperary. There’s a well here, and the ruins of an Augustinian Priory, and a ‘monastic trail’ which leads you to various stone ruins in what was once a flourishing monastic village, which began life in the fifth century.

Lorrha though, does have one thing that not many of these sites can boast: its very own home-grown saint. Ruadhán of Lorrha was Abbot at the monastery here in the fifth century, replacing his more famous contemporary Brendan the Navigator, who later discovered America ten centuries before Columbus. (Oh yes he did! Here’s a film about how he could have done it.)

St Ruadhán was one of the ‘twelve apostles of Ireland’, a collective of significant early Irish saints who studied under the legendary St Finian of Clonard. Ruadhán (whose name is pronounced ‘Rowan’, and means ‘red-haired’) was, like his fellow apostles, a monk of the Celtic tradition, which later came into conflict with Rome over various issues, like the date of Easter, the correct form of tonsure and other such theological details. In reality though, these issues were secondary to the real one, which was how much power Rome should have over monasteries in distant lands.

In early Ireland, Christianity was monastic, and it was Abbots rather than Bishops who called the shots. Irish monasticism had, for around 500 years, developed a specifically ‘Celtic’ character which seems to have been greatly influenced - and, I think, directly seeded - by Egyptian desert monks. This was the age of the round tower, the beehive hut and the small-scale, ascetic Christianity of the Wild Saints. It was the world of Patrick and Kevin, Colmcille and Bridget.

The Pontiff in Rome, however, wanted this scruffy, desert Christianity reined in under a hierarchy of Bishops answerable to him, and in Ireland, as in England a century before, the Normans would be his vessels. In 1066, the Norman king William the Conqueror (William the Bastard to his friends) had invaded England, killing its legitimate (and elected) King, Harold II, at the Battle of Hastings. He had done so under the Papal banner, which he had carried into battle, and on his victory he set about demolishing the old wooden Anglo-Saxon churches and building new, stone ‘Romanesque’ ones in their places. He also gave the green light to the continental monastic orders to move in and replace their indigenous counterparts.

A century later, in 1169, the now ‘Anglo-Norman’ barons who ran England (having stolen much of its land; someone once wrote a book about that) swept into Ireland, bringing with them the continental monastics - the Cistercians, Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinians - who were under the direct control of Rome. Monasticism was tidied up, and reined in. It was farewell to the green deserts of Ireland.

This was what happened at Lorrha, whose Celtic monks were replaced in the twelfth century by Augustinians, probably under the patronage of the new local Anglo-Norman landlord. The ruins of the Augustinian Priory can still be seen, probably on the site where Ruadhán had his earlier church:

Ah, well: history brings constant upheaval. It certainly did to Lorrha. As ever, its quiet facade belies its experience of violence. The Vikings, inevitably, sailed up the Shannon in the ninth century and trashed the place, and then Oliver Cromwell’s puritan army did much the same thing in the seventeenth. Violence was everywhere when Ruadhán was Abbott too. In fact, as a noted prophetic saint, he predicted some of it himself. When the pagan high king Diarmait profaned the church at Lorrha, Ruadhán prophesied both the death of the King and the collapse of his grand royal hall at Tara, which he placed under a curse:

Ruadhán gives the prophecy that Diarmait will be killed by the roof-beam of his hall at Tara. Diarmait has the beam cast into the sea. Diarmait then asks his druids to find the manner of his death, and they foretell that he will die of slaughter, drowning, and burning, and that the signs of his death will be a shirt grown from a single seed of flax and a mantle of wool from a single sheep, ale brewed from one seed of corn, and bacon from a sow which has never farrowed.

On a circuit of Ireland, Diarmait comes to the hall of Banbán at Ráith Bec, and there the fate of which he is warned comes to pass. The roof beam of Tara has been recovered from the sea by Banbán and set in his hall, the shirt, mantle, ale, and bacon are duly produced for Diarmait. Diarmait goes to leave Banbán’s hall, but Áed Dub mac Suibni, waiting at the door, strikes him down and sets fire to the hall. Diarmait crawls into an ale vat to escape the flames and is duly killed by the falling roof beam. Thus, all the prophecies are fulfilled.

If you’re thinking that the politics of the current moment is all over the place - well, it’s good to get a bit of historical perspective.

There might not be much to see in Lorrha now, but there is much to see in its past. And there are still interesting, quiet places to visit here. The well, for one:

St Ruadhán’s well is across the road from the ruined Abbey. It took a while to find it, because it is quietly hiding behind a stone wall. Stone steps lead down to what was once an eye well. There is no sign of veneration today, though the well is maintained by the locals.

Stare down into that black rectangle long enough, I think, and you could imagine anything. Vikings. Normans. Cromwellian soldiers. Or, indeed, something that was in fact found hidden under the well’s waters many centuries ago: St Ruadhán’s handbell. Possibly secreted there when the Vikings came roaring by, the bell, used by the saint to call his monks to prayer, is now in the British Museum. History is dissipated, its relics scattered to the four corners. But the land remains.

Your very well Well-Stories are my sunday treat. Will surely miss them when we're at 50. A few more weeks to dive along into all this, for me, eyeopening history. Thank you Paul.

Not trying to he dramatic but this reminds me of the one Supernatural experience I have had in my life. It was preceded by the sound of a bell. Just one clear ring, and it certainly got my attention. My guess is there will be bells in Heaven, maybe some wells too to hold that Water of Life.