St Ciaran’s Holy Well, Clonmacnoise, County Offaly

And so it is with moist eyes - and indeed feet - that we come to the end of our pilgrimage. What have we learned? I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’ve learned a good deal. About well rounds, cross stations, bullaun stones, big houses, burial rites, unbaptised children, curses and blessings, cement, high crosses, high kings, goddesses, virgins, floating stones, Desert Fathers, rosary beads, folklore collections and a whole army of indigenous saints. I don’t know what I’m going to do with myself on Sundays now.

Well, actually, I do have an idea - but more on that later.

For now, we find ourselves, as we did last week, at Clonmacnoise monastic site in the Irish midlands, ending our journey at a well named for St Ciaran, one of the nation’s most significant early Irish saints. Ciaran died in his early thirties of the plague and is buried at Clonmacnoise, but his work lived on for a thousand years, and his name still does. So does his well, which still springs fresh from the dark soil

You have to keep your eyes out for the little footpath that leads to it, which is just off the country road that leads to the monastery. I missed it the first time, and had to turn around. It is guarded by Scots Pines, and protected from wandering cows by a steel gate:

Inside is a small wooden structure, surrounded by ancient carved stones which perch incongruously on a base of garden centre gravel. This well is one of the last stops on a pilgrim path to Clonmacnoise which has been in use since the seventh century, making it one of the oldest pilgrim routes in Europe. St Ciaran’s well is also the first point on the local round of Clonmacnoise, which began here, circled the monastery taking in the stations of the cross at various points, and ended at St Finian’s Well, which we visited last week. This route, now fallen out of use, was known as the Long Station.

Arranged around the well itself are three intriguing and ancient stone carvings. It is not clear where they originated, but it seems likely they were taken from the monastery itself, which at its height must have been replete with beautiful stone.

The first is a weatherbeaten image of the crucifixion:

Then there is this one, which must be an early Christian grave slab taken from the monastery’s cemetery or from inside one of its churches. This design is common on early grave slabs:

Finally, and most intriguingly, is this strange stone:

It’s not clear on first sight what this could be, but some ferreting around reveals that it was once a human figure; its head has been taken by vandals. What remains is the body, featuring a strange kind of torc necklace. The suggestion is that this was once an ancient statue of St Ciaran.

Looming over all this stonework is a whitethorn tree on which hangs some prayer offerings. Beneath it, surrounded by wooden railings and its own stone wall, sits the well itself:

Sometimes it can be interesting to look deep into the waters of a well. It’s not uncommon for people to deposit coins and other offerings into the water. This time around, even from the top of the steps, I could see a white object in the water. You can see it yourself in the photo above.

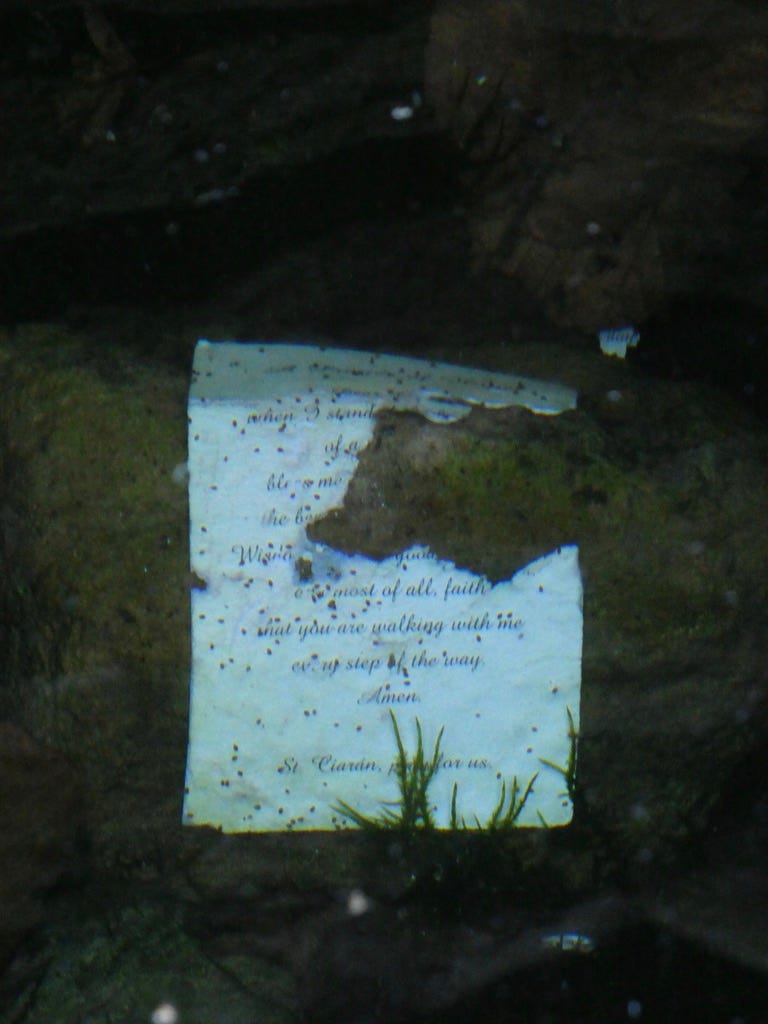

This is what it turned out to be:

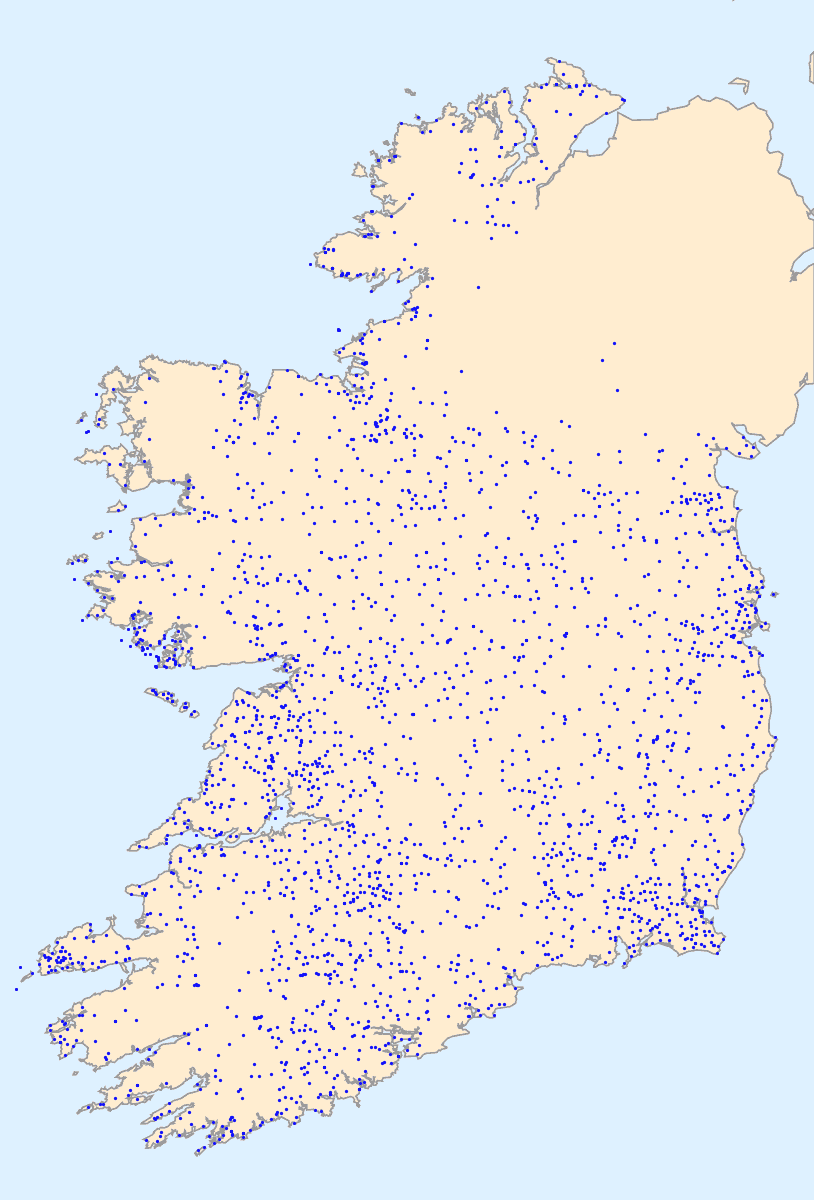

It’s torn, and mostly unreadable now - but this is a prayer to St Ciaran. Somebody brought it here - maybe they even wrote it - and deposited it in the well of this ancient Irish saint. As ever, the wells live. Clonmacnoise may be in ruins now, but these little, unobtrusive sites of folk devotion continue, in so many cases, to be living religious sites. And just look how many of them there are:

I know for a fact that there are wells out there which don’t feature on this map. Who knows - who can ever know - how many of these living sacred springs there are? And who knows how many are still visited and venerated, and what prayers are said there, and what comes from them? Nobody can know that. It’s one of the things I have loved about well-hunting.

These journeys I have made can seem light-hearted sometimes; a bit of fun and adventure and learning. They’ve certainly been that. Still, without wanting to make too big a deal out of it, I think I have learned something else about these living waters, too. I think that their continued presence in the Void of the Western anti-culture is not just some holdover from a dead past, but a potential pointer to the future. I’m very struck by how my own turn to the Eastern Orthodox Church, which in some obvious ways is very foreign to us in the West, is also a turn back, towards my own inheritance.

Here in my adopted country, all of the early saints and sites I have been writing about are still venerated in the Orthodox East, as well as in the Catholic West. The same is true of my ancestral homeland, England. It’s one reason I chose to end my pilgrimage at St Ciaran’s monastery. I began my travels at the well of St Colman, patron of the cave hermitage I have adopted as my own. I end it now at the well of St Colman, patron of the monastery in which I was baptised. In fact, I was baptised in a very cold Shannon, not far from this well. That monastery, the first Orthodox monastic house in this country for a thousand years, sits just across the river from here. St Ciaran has begun rebuilding.

Who knows what the future holds? Not me. But as the chaos of the Void accelerates, a parallel spiritual longing deepens. We need truth. We need God. People still come to the wells to speak to Him. I can see, if only in my dreams, a future in which more and more people come looking here. A future in which the wells are still tended and the prayers grow in numbers, the well rounds revive and the sacred landscape of ancient Ireland begins to awaken from its slumber. A future in which we remember that all things are soaked in God. A future in which the lessons of the modern hermit St Joseph the Hesychast are remembered by us worldly Christians today:

God is everywhere. There is no place where He cannot be found. Within and without, above and below, wherever you turn all things cry out: “God.” We live and move in Him. We breathe God, we eat God, we clothe ourselves in God. All things praise and bless God. The whole creation cries out. All things, living or inanimate, speak with wonder and glorify the Creator.

Who knows, maybe our tiny monastery here will be the first of many. Maybe the East will help revive the West. I have a feeling about it. All bets are off in the future which is coming. We are all on the Long Station together. But whatever happens, the wells are still out there. Holy landscapes abound. We make them holy with our prayers and presence. It is always up to us.

As for my future - well, as I say, I’ve enjoyed these little Sunday outings, and I’m already missing the actual outings that made them possible. I’m not old enough yet to sit at home drinking cocoa, and I’ve developed a taste for seeking out ancient, hidden holy places. So … I have a plan. Come back next Sunday, and I’ll tell you all what it is.

Until then: fare well.

I've really enjoyed this series, Paul. Thank you so much for sharing your travels with us!

This series has been fantastic, Paul, and very helpful to me as I have turned and left atheism behind.

I’m still a free agent and not sure what to make of the path ahead, but I look forward to your next project and all of the clues which will no doubt abound.

See you next month.