St Féchín’s Well, Lacken, County Galway

Last Sunday we visited the Ladywell in the neat little village of Abbey, in County Galway. This weekend we’re heading up the lane away from the village, past the old pub, past the henhouse, past the shop, and up into what passes around here for the hills. We’re not going far. We’re going to ramble just a couple of miles, up a few twisty lanes, by hedgerows and across streambanks and past isolated cottages until we reach another, quite different, kind of well.

But first we’re going to visit a cemetery. Wells and cemeteries - symbols of life, markers of death - are often to be found together, and here in St Féchín’s Cemetery, in the rural townland of Lacken, we find a particularly moving one. Not for the first time on our pilgrimage, we find ourselves standing on a mass grave.

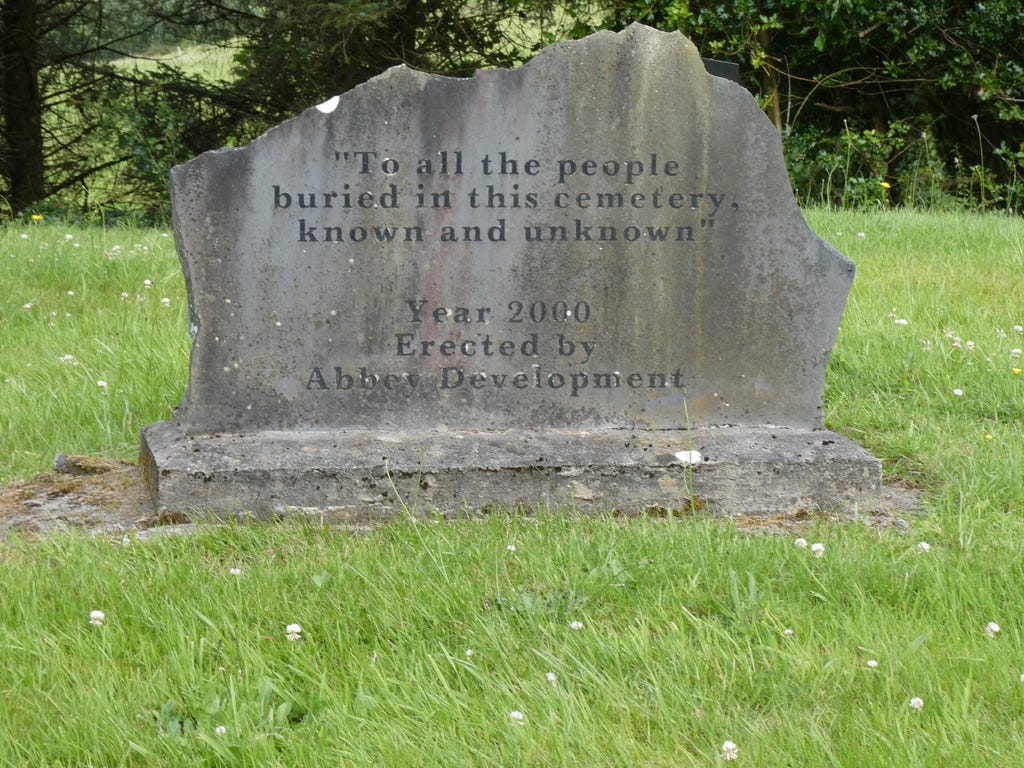

The last time I wrote of one of these here, it was when I found myself in a childrens’ graveyard, or cilliní. This time we are faced with something different. Local historians believe that a mass grave was opened up for use here during the Great Famine of the 1840s, which killed a million Irish people and caused a million more to flee the country. Memories of the famine still stalk every townland in Ireland. Here, a simple stone marks the spot where many of its victims were interred together:

This famine grave lies next door to a more conventional graveyard which is still in use today. Around the edges of the mound that seems to mark the mass grave, ringing the entire cemetery, are painted stones marking the fourteen Catholic ‘Stations of the Cross’:

This quiet, hard-to-find hilltop was once, according to the local historians, a significant holy site. It was here that St Féchín, a saint originally from County Sligo, built a small wooden chapel in the seventh century, which became a place of pilgrimage, as did its adjoining holy well, which was renowned, as so often, for the healing of the eyes. Féchín - whose patron day, in fact, was just yesterday - is today the patron saint of the village of Abbey, and an outdoor mass is still regularly held at this site.

The well is not in the cemetery, though. In fact, if you’re don’t know what you’re looking for you will be hard pressed to find it, as I was the first time I came here. There is no signpost and no footpath. You need to climb over the fence at the edge of the cemetery and make your way down the hill through the small patch of woodland towards a small bush in the field below. As you approach, you’ll see that the bush shades a pit in the ground with rough stone walls edging it. At one edge of the pit is what is presumably the well:

Step down into the hollow and gaze down into the well, as my daughter is doing here, and you will see that, in contrast to its local cousin down in Abbey, St Féchín’s well is in something of a sad state. The saddest state that any well could be in, in fact: it’s dry.

Given that this well sits in the centre of a field of cows, I wonder if the water table has been sucked low to provide drinking water for the bovines. They need a lot. But perhaps not: perhaps the well dried up of its own accord. Whatever the reason, a dry well just down the hillside from a mass grave is not the cheeriest of sights, even on a sunny day. The bush - once a rag tree - is empty of offerings, and it is clear that pilgrims rarely if ever make it here. Perhaps St Féchín does not enable cures in the way he once did.

Mind you, if historical rumour is to be believed, the medical interventions of this particular saint were not of the kind that any pilgrim would pray for. A quite un-saintly story appears in more than one historical source on the life of Féchín. Wikipedia, no less, provides a pithy summary:

A story about Féchín and the plague is found both in the Latin Life of Saint Gerald of Mayo and in the notes to the hymn Sén Dé (by Colmán of the moccu Clúasaig) in the Liber Hymnorum. It relates that the joint high-kings Diarmait mac Áedo Sláine and Blathmac mac Áedo Sláine appealed to Féchín and other churchmen, asking them to inflict a terrible plague on the lower classes of society and so decrease their number.

This is the kind of thing that Irish kings used to do, back in the day. They were an unsentimental lot, and were not above a bit of mass murder if it suited their needs. You would, of course, expect a holy man to refuse to join in. Unfortunately, the stories tell us that Fechín instead assented to the request, and began praying for the Lord to bring down a deadly disease upon society’s undesirables.

This story may just be a scurrilous rumour planted by his enemies, of course. We are not likely to ever know the truth either way. But one thing the sources do agree on is that soon after this incident, the saint died - of the yellow plague. Coincidence, irony - or an answered prayer? We will never know that either, but as the Irish might advise: you should always be Féchín careful what you pray for.

The whole way through I was waiting for the Féchín joke 😆.

Great post! I'm really enjoying this series on holy wells. Thanks Paul