The best thing I ever bought was my VW camper van. It came into my life soon after my first child, and the two have grown older together. Neither of our children would allow us to sell our old van now even if we wanted to; there are too many memories tied up in it. That van has been with us on beaches and in woodlands, on hills and plains and mountains, on ferries and in lay-bys too numerous to count. I’ve got it stuck in mud, reversed it into trees, blown out its tyres on hidden rocks and exploded several of its gaskets in several different nations, and it’s still more reliable than me.

In the age of covid, our family van has allowed us to escape on little holidays in our own country, with the added advantage that we can avoid the various establishments that we are now banned from by our ever-caring authorities. In the west of Ireland you can squirrel yourself away down a lane or on a remote beach, and nobody will bother you if you’re tactful. In human-scale places, you are still mostly free to be human.

It was quite recently, a few weeks back, on a short family trip in our van, that I saw something about my world, and by implication myself, that I haven’t been able to unsee. Sometimes this happens to me, as I’m sure it does to many of you: something that you believe you ‘know’ in some abstract, intellectualised sense becomes suddenly real in a more embedded way. You see it playing out, sinking in, and then it is no longer an abstraction but the pattern of your reality.

On this occasion we were in a small town - a nice little place, full of holidaying people like us. There were pubs and restaurants open, and the streets were full of tables and chairs (one of the unexpected benefits of the pandemic has been that Ireland has discovered outdoor dining). There were shops and markets. There were people in vans, like us, and other people hiring boats and other people eating and drinking. There were leaflets in the tourist information centre advertising country house tours and chocolate makers and cycling trips.

It was a nice little place, and all of a sudden I saw it for what it was. I saw what was happening here, and by extension everywhere, and within me and all of us. I saw that everything around me was dedicated solely to the immediate gratification of the senses.

There it was, all of a sudden, right in my face. Eating. Drinking. Buying colourful things. Boats, vans, bikes, beer, steak, new clothes, second hand clothes, burgers, chocolate bars, old castles, stately homes, cappuccinos, pirate adventure parks, golf courses, spas, tea rooms, pubs. Food, drink, fun, entertainment, games, probably some sex somewhere in the mix. All of it came together suddenly into a kind of package of sensory overload and I saw that this was what we were, what we had become without really thinking or planning it. Stimulating the senses, then reacting to the stimulus: this was what our society was all about. Feeding the pleasure centres, spending and spending to keep it all coming at us.

It was a nice little place. A small, unremarkable town that became, just for a second, the centre of the whole world.

None of this stopped me from enjoying the rest of my holiday. I ate crisps and went kayaking. We drove our camper van around the coast. But somehow, a part of me remained - still remains - cut off from it all, observing as if from a distance this situation and its consequence: the ongoing degradation of the world. A process I am part of, even as I complain about it. Even as I see what is happening, I put my shoulder again to the wheel that turns it all around.

This is what a Machine society looks like. It is all a kind of simulacrum of a real culture, with organised sensory gratification replacing anything that might previously have provided lasting meaning. I don’t mean to imply that sensory gratification is anything new - or even anything inherently bad, within reason. We’re all human, and that’s still (mostly) OK. Since at least the Neolithic we’ve been adorning ourselves with imported foreign jewellery and roasting meat to perfection. The pursuit of sensory pleasure certainly took up most of my younger life, even though these days my main vices - the public ones, at least - are chocolate and cheese.

But the pursuit of instant pleasure as an organising principle of society? A culture that is becoming little more than a Pleasure Dome, dedicated to ‘growth’ and a supposedly consequent ‘happiness’? This is something that ought to bring about more than moral doubts.

If you think I’m going over the top here, then it’s worth zooming out. The impacts of a society predicated on boundless economic growth via boundless sensory stimulation are at least in some ways measurable. Visit this website, for example, and you can see a real-time counter which will tell you just how much waste has been dumped around the world this year as a result of this way of living. At the time of writing, the counter is reading 1.4 billion tonnes. It’s only September.

We can enjoy our little towns here in the richer bits of the world because the waste we generate through our excitable purchases of big-screen tellies, lego sets, foreign holidays, cheap clothes, cheap food and all the rest of it always ends up somewhere else. The dioxins and PCBs go into the water and soil, the plastic goes into the oceans, the carbon dioxide goes into the air. Fifty million tonnes of ‘e-waste’ is shipped every year to the poorest countries on Earth, which are least equipped to deal with it. But then they’re not really supposed to deal with it: they’re supposed to keep it away from us. We don’t know what else to do with all this crap, so we - for example - ship 4000 tonnes of toxic waste, containing carcinogenic chemicals, to Nigeria, and just dump it on the beaches. The same way we dumped 79,000 tonnes of asbestos on the beaches in Bangladesh, and 40 million tonnes of our poisonous waste in just one small part of Indonesia. The same way we run our old ships up onto the beaches in China and India, and leave them for the locals to break up - if they can. The same way we dump nine million tonnes of plastic into the oceans every year.

Had enough yet? Me too. But we need to understand the consequences of the Machine we have built, and which is now rebuilding us so that we may become more perfect consumers, shopping for individual fulfilment in its Global Marketplace of goods, ideas and identities. We need to understand just what this Machine encourages within us, what it inflames and what we have become: a cheap, digitised version of Late Rome, looking elsewhere when the container ships take away our mess to be dumped on the poor.

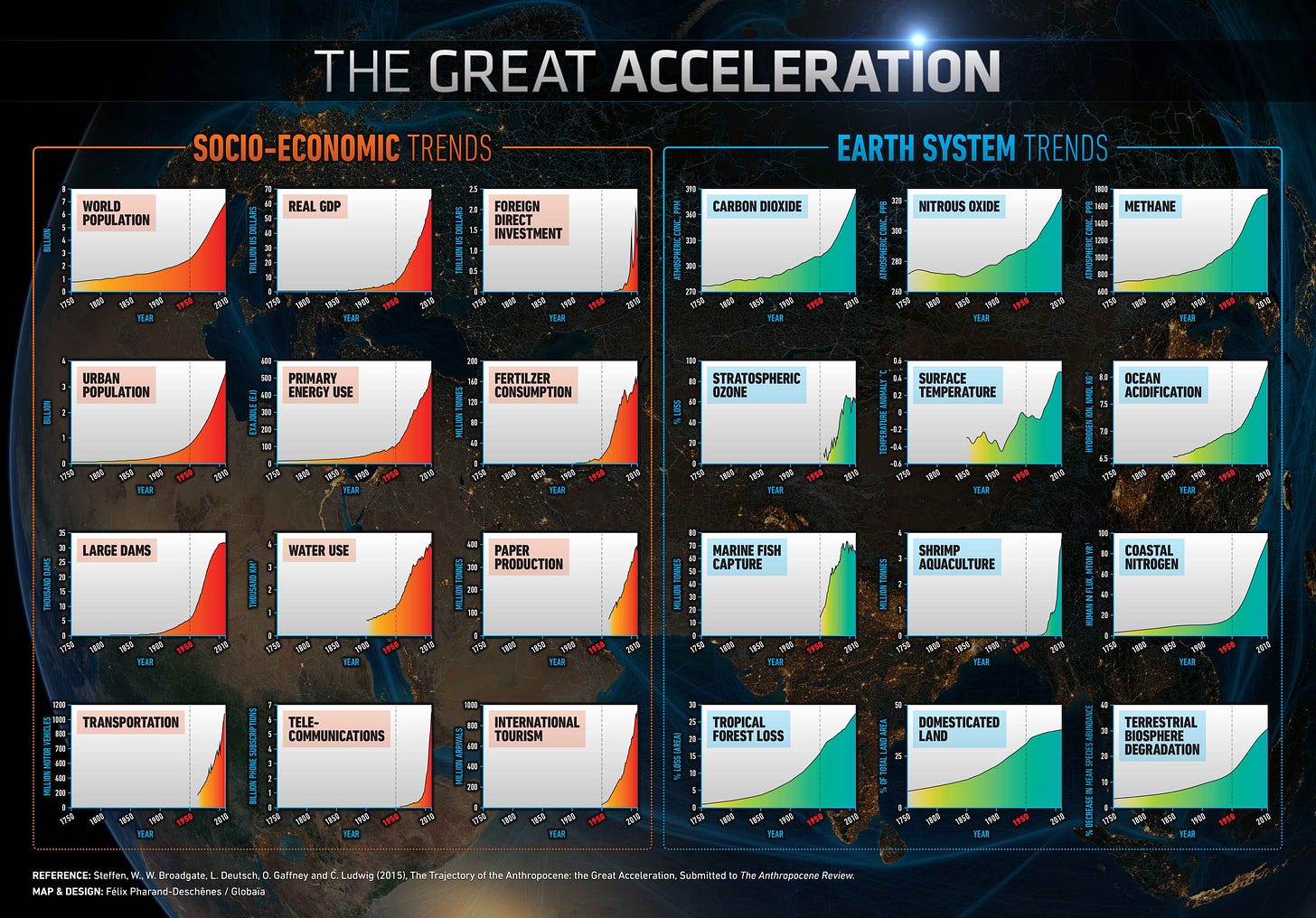

I’m not usually one for graphs, but the illustration at the top of this page gives a historical perspective on all of this. All of this abundance comes from the bonanza of fossil fuels that enabled the industrial revolution to take the Machine global (more on that next time.) The size, scope and speed with which we are eating the Earth and turning the results into toilet paper, plastic ducks and smartphone batteries is unprecedented and, in historical terms, very new.

If you look closely at the charts above, you’ll see a number in red in the baseline of each of them. This is a year: 1950. It marks the beginning of an age of rapidly-accelerating economic growth, fuelled by mass production and mass consumption: a period that has been dubbed the ‘Great Acceleration’. The lines on these graphs - each of them virtually identical, shooting almost vertically upwards over just the last seventy years - are the story of our age. In just one human lifetime this has changed virtually everything. I believe that the West’s current cultural disintegration is another result that, if we knew how to measure it, could probably be staked out on a similar chart. A culture that believes in little or nothing beyond the stimulation of the senses is at the end of its useful life.

In two previous essays - you can read them here and here - I attempted a historical thumbnail sketch of how the process of Machine modernity got us to this point: the end of the Christian faith in the West, the rise of ‘Science and Reason’ (which were, however, a product of the Western version of that faith), and the revolutions of 1789 and later, which, by clearing the ground of the last remnants of feudalism, laid the foundations of a new kind of world, governed by a new kind of people, with a new set of values.

Those people - well, they’re mostly us. The best and most poetic chroniclers of their - our - revolution remain Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who, whatever their other flaws, have never been bettered in their description of the new world which grew from the ruin of the old, and which is now coming to ruin itself. A world with new values: growth, progress, profit, money. A world built by the most revolutionary class in history, one which embodies these values and has embedded them, over the centuries, into every aspect of our lives: the merchants, traders and moneymen otherwise known as the ‘bourgeoisie’:

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his "natural superiors," and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous "cash payment." It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value. And in place of the numberless and feasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom - Free Trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

This description is, famously, from the 1848 Communist Manifesto. It’s a curious document, world-changing in a way that few pamphlets ever are. Curious, to my mind, because it is a hearty damnation of the world the bourgeoisie have built, but a damnation which is tinged with a sneaking admiration. Marx and Engels, after all, were both self-styled revolutionaries. As such, they recognised that the capitalism they set out to destroy was the most effective revolutionary force in history. The ‘bourgeois’ class which drove it on, they wrote,

… has accomplished wonders far surpassing Egyptian pyramids, Roman aqueducts, and Gothic cathedrals; it has conducted expeditions that put in the shade all former Exoduses of nations and crusades … It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers. The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil, and has reduced the family relation to a mere money relation.

Revolutionary stuff indeed. And this bourgeoisie had revolutionised not just the structures but the values of humanity, at the deepest levels:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society … Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

Everlasting uncertainty and agitation. Today’s world was under construction- globally - even back in 1848. Once the bourgeoisie really got to work, the current age of corporate globalism - and the waste, destruction and cultural decay it generates - was the inevitable result:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere. The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world-market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country … It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

I’m no Marxist, but the Communist Manifesto describes the world we are in with brilliant prescience, despite being written nearly two centuries ago. The Great Acceleration is the natural conclusion of the world which Marx and Engels saw being born, and pinioned in words so well. Once the ‘bourgeois revolution’ had cleared the ground of awkward obstacles like the peasantry, the artisans, common land, local cultures and traditions, family and home life, a sense of history and mutual obligation, and religions which preached against wealth and wordly power, then the captains and priests of the Machine could get on with the work they were made for, the work of our time, the holy effort to which all human will, skill and energy is now bent: making money.

I could, I suppose, cant on about the ‘bourgeoisie’ all day, but it would start to sound like either a branch meeting of the Socialist Workers Party or a Monty Python sketch. What I am really trying to get at here is not a theory or a structure or an ideological claim, but something deeper: an old, surging force, one that stems from within us. A force which has driven all this onwards, which is the lifeblood of the Machine, and which, through its untrammelling, acts as an acid which burns through all past structures and values. An acid which is now acting to dissolve our ecosystems and cultural forms, as it has dissolved so much else.

What is this force? What could be so powerful that it could dissolve away centuries of our cultural inheritance; could dissolve forests and oceans, great faiths, nations, traditions - everything that makes a human life real - and replace it with this … Pleasure Dome?

Want. Want is the acid.

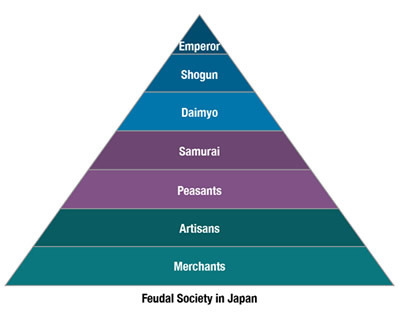

We can usefully understand our time, I often think, by seeing in it the final result of the centuries-long tension between the merchant class - that ‘bourgeoisie’ - and everyone else. Pre-modern societies, in every case that I know of, always kept the merchant class in their place, and that place was usually right at the bottom. Here, for example, is the social pyramid during Japan’s Edo Period:

The merchants sit right at the bottom, below the farmers and artisans, because their work, while sometimes necessary, essentially created nothing of value. This was the pattern worldwide. In medieval Europe, usury - the lending of money at interest - was a sin, as it still is in Islamic nations. Here too, the merchants, bankers and money people were hemmed in by a network of customs, religious edicts and structures like guilds and professional bodies. Money had to be kept under control, precisely because of the power it had to ignite the powerful flame of want.

I’m not especially suggesting we should all live under a Shogunate, though at least it would give us elites with some panache. But the story of the world since the eighteenth century has been the story of the setting of that flame, and the resulting fire. We are all bourgeois now: which is to say that we are all driven forward by want. Even those who see the dark side of this world will often promote it anyway, even as just a temporary expedient. In a famous essay from 1930 - an essay which is in many ways an advert for the utter failure of the modern ‘science’ of economics - the British economist John Maynard Keynes explained that it might take another century to solve ‘the economic problem’ worldwide, ensuring the end of poverty and the creation of a wealthy, leisured modern planet. When that happened, we might again become virtuous as a society:

I see us free, therefore, to return to some of the most sure and certain principles of religion and traditional virtue - that avarice is a vice, that the exaction of usury is a misdemeanour, and the love of money is detestable, that those walk most truly in the paths of virtue and sane wisdom who take least thought for the morrow. We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin.

This Utopia, however, would take a while to reach, and until it was reached, we would have to pursue ‘growth’ regardless of the short-term cost:

But beware! The time for all this is not yet. For at least another hundred years we must pretend to ourselves and to everyone that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not. Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still. For only they can lead us out of the tunnel of economic necessity into daylight.

There is the Devil’s bargain, in black and white. It’s nearly a hundred years now since Keynes wrote those lines. How are we doing at solving his ‘economic problem’? The Great Acceleration answers that question simply enough, and the record rates of absolute poverty and inequality seal the deal. When we look around us, we can see that Keynes’s naive notion - that a society which cores itself around ‘avarice and usury’ can suddenly drop those vices when some undefined plateau of perfection is reached - is ludicrous. Once you adopt these values, they will make and remake you. The world they have built will depend upon them being pursued forever.

Four decades after Keynes made his claim, another British economist, E. F. Schumacher, skewered his assumptions in his book Small Is Beautiful. Taking issue with ‘the dominant modern belief’ that the kind of ‘universal prosperity’ narrowly defined by the likes of Keynes would lead to peace or happiness, Schumacher suggested instead that entirely the opposite was the case:

I suggest that the foundations of peace cannot be laid by universal prosperity, in the modern sense, because such prosperity, if attainable at all, is attainable only by cultivating such drives of human nature as greed and envy, which destroy intelligence, happiness, serenity, and thereby the peacefulness of man.

This made the question of ‘prosperity’ a much bigger issue than the likes of Keynes had suggested:

What is at stake is not economics but culture; not the standard of living but the quality of life. Economics and the standard of living can just as well be looked after by a capitalist system, moderated by a bit of planning and redistributive taxation. But culture and, generally, the quality of life, can now only be debased by such a system.

This is a big claim. It is also, to my mind, obviously correct. Schumacher knew it, and Keynes knew it too: it’s why he so apologetically explained that we would need to live under a self-made spell for a hundred years, like some fairytale princess. We must pretend to ourselves and to everyone that fair is foul and foul is fair. What he didn’t forsee was that we would forget we were pretending. Today we are led by want, we are drenched in it, and we are increasingly sick from its infection.

What is interesting about both Schumacher and Keynes’s approaches to the plague of want is their almost religious language: or in the case of Schumacher, a Christian inspired by Buddhist principles, their openly spiritual perspective on the problem. There is a lot of talk here of sin, of wrong and right, of fair and foul. In this, both men distinguish themselves from today’s economists, for whom talk like this is embarrasingly passé. We are all grown-ups now, and we know that living by want is not only necessary but can be justified with software modelling and leader columns in The Times.

But a value system which glorifies wealth and accumulation, which builds itself on a platform of want, which inflames and creates more of it daily through a marketing machine which colonises the human mind - this is what every spiritual tradition in history has warned against, and with good reason. Take, for example, the famous list of the Seven Deadly Sins in the Western Christian tradition: gluttony, lust, pride, wrath, greed, sloth and envy. With the possible exception of sloth, we currently live in a culture which not only sees nothing wrong with these values but actively encourages them. The pursuit of these six vices is no longer something to be confessed or repented: it is the very thing which drives our notion of Progress forward.

So this is who we are. You don’t have to be a Christian - or a Buddhist - to see where it has led us, and where it will lead next. Want is the acid. Capitalism is the battery. Growth is the engine. Greed is the forming energy that moves us to where we are inevitably headed.

What is the brake?

The answer is as hard as it is old-fashioned. I have come to see that all of the questions raised in these essays - the questions raised in my lifetime of non-fiction writing, and maybe my fiction too - could be said to come back to one word: limits. Modernity is a machine for destroying limits. The ideology of the Machine - the liberation of individual desire - sees our world as a blank slate to be written on afresh when the old limits of nature and culture are washed away. This is our faith: that breaking boundaries leads to happiness, that boundaries are barriers rather than opportunities. We strain against all limits. It is who we are.

What Schumacher knew but Marx denied - with all the terrible consequences that the twentieth century produced - was that the solution to the triumph of want, as far as there can ever be one, is not political revolution followed by a grand new social structure, but something harder and less spectacular: spiritual vigilance. The problem of want can be guided by systems and cultures, but it is, ultimately, a matter of the heart. Want will dissolve everything, if we let it, and new structures will not prevent that. Guarding the heart is the best defence against the acid.

Want is the acid, but the heart is both its provenance and its potential enemy. I often ask myself: Do I want too much? Do I grasp too hard? Do I live too heavily? The answer is always yes, and in spades. Plenty of people don’t have the luxury of asking these questions. I think this gives those of us that do all the more obligation to work them through.

Fortunately, we don’t have to do it alone. ‘It is hardly likely,’ wrote Schumacher, in the conclusion to Small Is Beautiful, ‘that twentieth-century man is called upon to discover truth that had never been discovered before.’ The dangerous results of untrammelled want have been known since the dawn of time, which is why every sane culture has discouraged it rather than making it the basis of its value system. But an ancient problem, as Schumacher’s closing paragraph emphasised, will have ancient solutions - if we choose to go looking for them:

Everywhere people ask: “What can I actually do?” The answer is as simple as it is disconcerting: we can, each of us, work to put our own inner house in order. The guidance we need for this work cannot be found in science or technology, the value of which utterly depends on the ends they serve; but it can still be found in the traditional wisdom of mankind.

_________________________________________________

You can hear me talking a bit more on these themes, and diving into the ‘theology of the Machine’ in this recent interview. There is more of this kind of thing, and more to come, on my Youtube channel.

Truth to tell, upon reading this provocative posting, the now deceased Malcolm Muggeridge and his prophetic voice came tumbling into my mind, ressurected, pell-mell, cutthroat and pistol!

Paul has indeed taken on a similar role, as a prophetic and critical voice during these troubling times, but his voice is uniquely distinct from that of Muggeridge, in that Pauls approach is coloured with the majestic mysteries and wonders of nature and how poorly we humans have stewarded this fragile planet we share together.

Here then is a brilliant sampling of Muggeridge and his penchant for prophetic narrative, bristling with irony, intelligence and wit:

“So the final conclusion would surely be that whereas other civilizations have been brought down by attacks of barbarians from without, ours had the unique distinction of training its own destroyers at its own educational institutions, and then providing them with facilities for propagating their destructive ideology far and wide, all at the public expense. Thus did Western Man decide to abolish himself, creating his own boredom out of his own affluence, his own vulnerability out of his own strength, his own impotence out of his own erotomania, himself blowing the trumpet that brought the walls of his own city tumbling down, and having convinced himself that he was too numerous, labored with pill and scalpel and syringe to make himself fewer. Until at last, having educated himself into imbecility, and polluted and drugged himself into stupefaction, he keeled over--a weary, battered old brontosaurus--and became extinct.”

If we follow the Desert Fathers and see sloth not simply as laziness but as an ever-enveloping apathy to all commitments we've made, I'd say the Machine has all seven sins covered for us.