It is the forward motion that matters - in the writing of a book as in a spiritual life. Or any life. It is the movement towards the radiant city that powers the narrative and keeps the interest. Without the onward trudge - sometimes entrancing, sometimes miserable - there would only be stagnation. A book must be a journey, and a journey will always become a story.

Why has The Way of a Pilgrim become, as is so often claimed, not least by its publishers, ‘a spiritual classic’? It is, I think, because of this movement. To understand what I mean, try to imagine this book without the actual pilgrimage. Imagine that, rather than going out walking, the nameless seeker at the heart of the story had just stayed at home, read his Bible and his Philokalia, gone to church on Sundays, spoken to his priest and practiced the Jesus Prayer alone in his cabin. What would the book be then? Perhaps it would still be a useful prayer manual, or even an interesting Christian text of some kind. But it would hardly have gained the grasp on the spiritual imagination that it has built up since it first appeared.

The genesis of this book is a mystery - which might be another reason for its intriguing reputation. The manuscript apparently ‘turned up’ at a monastery in Mount Athos in the nineteenth century. Quite how this happened I don’t know, and I’m not sure anyone else does either. The really intriguing question is whether this book represents an account of a real journey written by a real person, or is instead fiction, or a spiritual allegory of some kind. The fist time I read it I assumed it was the latter, but these days I’m not so sure.

An argument in favour of it being the account of a real journey is another reason for the book’s appeal: its naïveté, in the best sense of that word. If this were a novel, an editor would want to have words with the author. By any kind of conventional literary standard, it is not well constructed. Certainly no mainstream publisher today would put out a book like it. It has no obvious arc - no beginning, middle or end. There is no ‘character development.’ There is no jeopardy. Events happen to the narrator which seem to be building up to something, and then … they don’t. He just keeps walking. There are long passages in which the art of prayer is discussed in detail, for pages. At the end, the narrator seems to be heading towards the climax of his story, as he sets out for Jerusalem. Then the book just stops.

As a ‘professional writer’ I ought to disapprove of all this, I suppose, and long for something more polished. In fact, the opposite is the case. I am sick to death of clever, supposedly well-constructed books that say nothing, or just parrot the toxic cultural drivel of the age. I’ll take something pure and clumsy any day of the week over whatever is winning all the prizes at the moment. The last shall be first, and all that. We need more pilgrims in this world, and fewer professional writers. More spiritual culture and less literary culture, thanks very much.

Another argument for the reality of the story in question is the follow-up. The book is often published today with a sequel entitled The Pilgrim Continues His Way. Purporting to be a continuation of the story, it is quite different in tone and content. Much of it is essentially a long argument about prayer, sprinkled with a fair bit of theology and detailed instruction. There is little or no forward movement to it. One theory has it that the the original Way is a genuine account of a pilgrimage, while the sequel was written by an Athonite monk, hence its more didactic and theological feel.

Either way, what we have in The Way of a Pilgrim is two intertwined narratives, each powering the other. One is about a spiritual pilgrim searching for the secret of prayer. The other is about a literal pilgrim seeking to strip away everything unnecessary from his life, and to move through the world unencumbered, meeting it as it is. As I say, the complete lack of guile in the telling of the tale is one of the reasons I love the book. It’s not simply the naïveté of the telling, but the quality of the landscape and its people which draws me. I find myself wondering, wistfully, what it would be like to live in a country and a time when wandering around as a poor Christian pilgrim would be an explicable life choice. What it would be like to meet people and have long spiritual conversations in taverns and houses and woodlands. What it would be like to exist in a time and place which was soaked in God, rather than entirely emptied of him.

What would it be like, too, to be the sort of person who can meet anything that the road brings him with equanimity? One of the key features of the narrator’s personality - one which that contemporary book editor would certainly complain about - is his lack of passion. He meets the world as it is, whether it includes rich people housing him for their edification or attacks by wolves; wrongful arrest or unexpected employment; beatings by bandits or hours in green woods reading in peace. Our pilgrim takes it all as it comes. Everything is treated as an opportunity for a spiritual lesson.

Is this ‘realistic’? Well, for some people, yes. There are people like this - or, to be more accurate, there are people who learn to become like this, usually through travail. Often we call them ‘saints.’ Significantly, our nameless pilgrim had a worldly life before his journeys begun, but like Job, he lost it all. An inheritance, a house, a loved and loving wife, a place in the world: all have been stripped from him. But instead of being consumed by sadness or bitterness, the pilgrim has realised instead that the world can never satisfy him. He has to go within, to the only place he can find God, the still point of the turning world. He walks away from the world by walking straight through it.

I have always been attracted by lost worlds. But again, we have two worlds on show here: the outer one through which the pilgrim wanders, and the inner one, which he seeks the secret of prayer to ignite. Ten years ago, it would have been the outer journey which interested me. The long and solemn conversations about hesychasm would have bored or baffled me. These days, I can’t get enough of them. The search for holiness is the thing: the pearl without price, the only mystery left. When the pilgrim is asked by a wealthy judge he is staying with what he is wandering for, he tries to explain it like this:

The fact is that we are alienated from ourselves and have little desire really to know ourselves; we run in order to avoid meeting ourselves and we exchange truth for trinkets while we say ‘I would like to have time for prayer and the spiritual life but the cares and difficulties of this life demand all my time and energies.’ And what is more important and necessary, the eternal life of the soul or the temporary life of the body about which man worries so much? It is this choice which man makes that either leads him to wisdom or keeps him in ignorance.

This either chimes with you, or it doesn’t. If it does, then the pilgrim’s search for contemplative prayer, through the Eastern Orthodox tradition of hesychasm - inner stillness - is going to teach you something. Approach this book with a literary head, on the other hand, and you may be disappointed. Approach it as a fellow seeker, a fellow pilgrim, and every time you read it something new will jump out at you. Whatever it is that jumps out will probably have something to say that you need to hear.

This time around, for example, I quickly noticed this passage:

My late elder used to say that obstacles to prayer come from two sides, the left and the right; that if the enemy does not succeed in turning us away from prayer by vain and sinful thoughts, then he brings to mind instructive and beautiful thoughts only to turn us away from prayer, which he cannot tolerate.

This sounds familiar to me. Familiar too is the accusation which a priest makes to our pilgrim in the book’s sequel, after the pilgrim has confessed his sins:

You enumerated all the trivialities but ignored the most important thing; you did not reveal your serious sins. You did not acknowledge and did not write down that you don’t love God, that you hate your neighbour, that you do not believe in the word of God, and that you are full of pride and ambition. The entire abyss of evil and of our spiritual corruption lies in these four sins. They are the main roots from which spring the shoots of all our other failings.

It’s a fair cop. When I sit and look into my heart, this is more or less what I see. When I look into this book, on the other hand, I see the thing that pulled me into Eastern Orthodoxy, rather than into any other manifestation of the Christian faith. The profound and very ancient practice of inner stillness is still practiced today: in fact, it is probably more widespread in the Orthodox world than it was during the pilgrim’s time, not least because of the publication of this book. Just two years ago, I was approached by a Schemamonk during a trip to a Romanian monastery, and was offered, unbidden and through a translator, a miniature masterclass in how to pray the Jesus Prayer. This tradition is still alive. This, to me, is the real thrill.

The pilgrim, on his way, is stumbling at his own speed towards the Radiant City. The more he prays, the more prayer leads him towards a kind of plain and joyful renunciation of anything and everything that might keep him from that goal. In this, the pilgrim is achieving through practice what I was trying to write about in my last essay here: the work of dying to the world. The more he does so, the more he achieves the ultimate Christian virtue: humility. We know that he is closing in on it because he is sure that he would never reach it in a million years.

That’s my take, but I’d like to hear yours. I know from the chat thread that some of you had a very different reaction to the book. Leave your own short reviews below, or post a link to a review you may have written elsewhere. The chat thread also remains open for conversations about the book.

AND OUR NEXT BOOK IS …

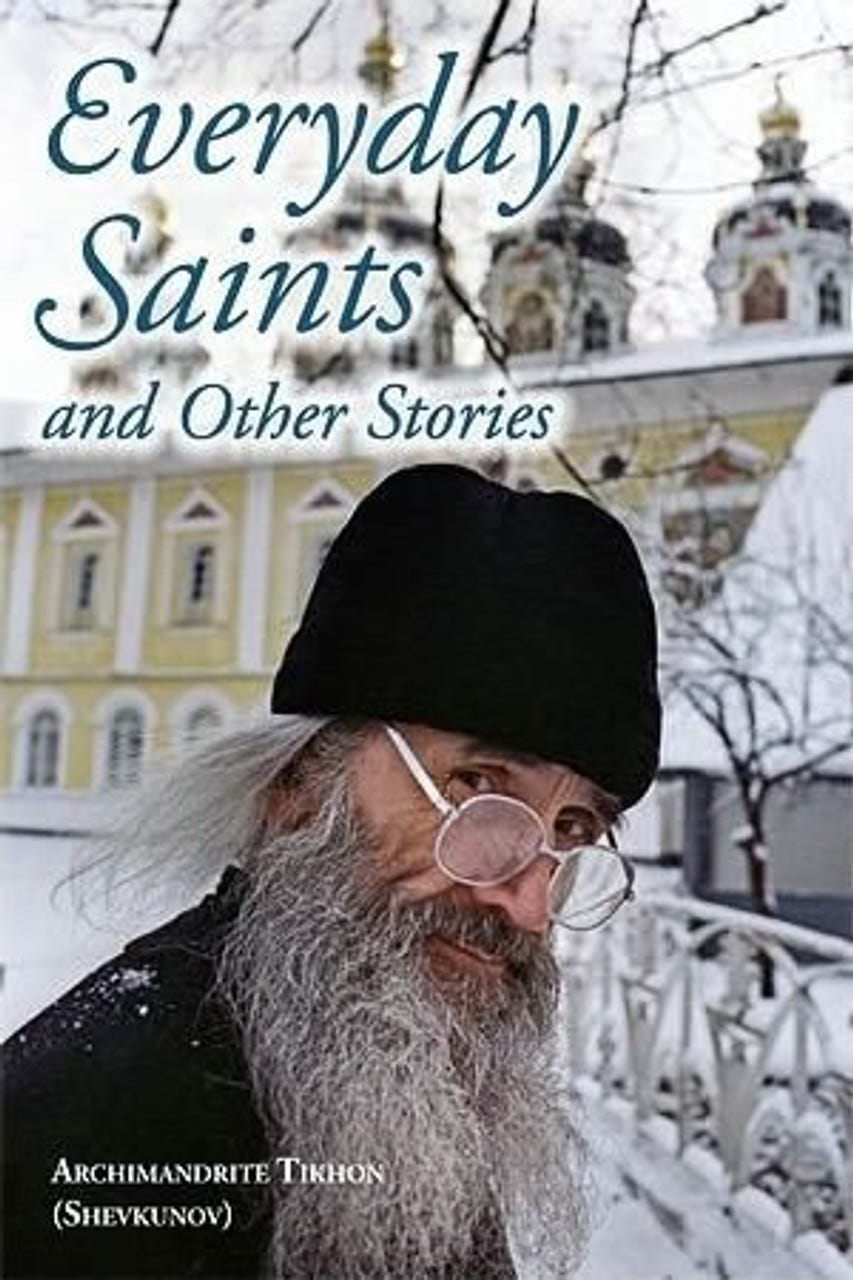

For the Scriptorium’s second book, we’re staying in Russia but bringing things up to date. I’m going to be reading and reviewing Everyday Saints, a book that was published just thirteen years ago, and which managed the impressive feat of selling a million copies in its first year. It’s long been a bestseller in Russia, and now it’s gaining a reputation outside the country too.

Everyday Saints is the story of five young men, none of them from religious backgrounds, who took the radical step of becoming monks at one of Russia’s oldest monasteries during the reign of the USSR. The book tells the story of what happened to the five companions on their journey, the people they met and the lessons they learned. Unlike The Way of A Pilgrim, I’ve not read this book before choosing to review it here, so I have no pre-formed opinion. I’ll be coming to it as fresh as any of you who choose to join me.

My review of Everyday Saints will be published here on Monday 1st July. As ever, I’d love to hear your responses, or to read your own reviews, either in the comments here or on your own sites. A new chat thread about the book has just been opened.

Just three days ago I went on a pilgrimage from my home, in Barcelona, to Montserrat, some 50 kilometres away. The reason was a vow I made last year to the Theotokos. I spent 12 hours straight walking. I'm a Roman Catholic but I have learned a whole lot from the Orthodox tradition, which I cherish very dearly. As you say, and as The Way of a Pilgrim also attests (I read it during Catholic Lent this year) walking has a type of universal truth that scorns mere logical propositions.

I had time to pray the Rosary, the full fifteen mysteries, to say the Jesus Prayer countless times, to reflect, to sing to myself and to enjoy silence. By the end of it I didn't feel any elation or catharsis, there was no sense of achievement.

Some time ago, I might have worried because I've been raised in a culture that puts a premium on emotions and things that 'feel good' but the Christian tradition, and the Orthodox are particularly emphatic on this, tells you not to give importance to such stuff. It tells you that love is most of all what you do, not what you feel. Praying is at the heart of that. Right next to it is walking, because that is the purest expression of the state of us in the world, which is exile. If The Way of a Pilgrim is about something, that's it. Wandering in exile. If modern editors don't like it, that's because they've learned to expect redemption in this world, a closed sense of structure that begins and ends here. This overpowering desire to square the circle is, I guess, what you so aptly described in your Machine series. The Machine will never understand the Pilgrim just as surely as Sauron never understood Frodo's quest. But then again, that's why it will ultimately fail.

Thank you, Paul.

I finished reading the book about three weeks ago and have been waiting for the day of your opening review to arrive. I, too, am on a journey to discover what my faith is and should be. And to work out whether I can actually justify calling myself a Christian. I wrote in a previous post that I found the book irritating. The reason won’t surprise you. If everyone were that pilgrim, then where would be the rich men able to provide the food and shelter he needs, as he makes his way wherever he is going. Literally his can’t be the only way. But that’s a very obvious reaction. I imagine many readers will have had it too.

I understood your lesson about being “dead” to the world. But the pilgrim seemed to be demanding so much more. That one make prayer the only thing in one’s life. I’m not sure if I even like the idea of prayer. It seems so inward focussed and, the way he writes about it, almost like an addiction. I equate it with the modern preference for meditation. A shutting out of the world, when I think belief is all about how we accept and cope with the horrendous challenges and imperfections of that world., which we are lucky enough to have been given a brief chance to inhabit. We need to face into it, not away from it.

The key experience in my “pilgrimage” so far was a weekend on a course run by your friend Martin Shaw, during which he told the tale of Dairmud and Grainne. It’s the tale of a love triangle that goes on for the whole adult lives of the characters, starting with the woman, Grainne, rejecting and humiliating the older suitor (Finn) in favour of a younger man,(Dairmud) who was like a son to Finn. In the middle of this story is an incident of random, completely pointless cruelty, where Grainne (otherwise the heroine of the story) deliberately flaunts her physical relationship with Dairmud in front of Finn. Mayhem results. Dairmud dies. At the end of long lives riven with conflict, jealousy, egotism and violence - Finn and Grainne finally finish up together in old age, forgiving and forgetting everything that has been done by both of them. Had Grainne made a different choice, this peaceful and happy life with Finn is the existence she could have enjoyed all along. But life being what it is, she was never going to make that different choice.

The lesson I took from this was profound. And fairly obvious. Life is imperfect-able. There is not and never will be a utopia, because human nature is what it is. The world isn’t divided into good people and bad people. Even the best people do stupid, hurtful, terrible things. The only thing each individual can do is learn to survive them. By being, as you said, “dead” to the world. One cannot live a good life, unless one is able to rise above setbacks and cruelties and disappointments. But we can’t. So all we can ever do is keep trying.

Coming back to my own spiritual journey. I guess what I recognise about Christianity is the liturgy that begins with a recognition of ones own sins and shortcomings. I like saying the same things every week or every time we are in church, because those things will always be true. We will have “sinned” “through weakness, through negligence, through our own deliberate fault”, as others will have sinned against us. And we will have to pray for forgiveness of “our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us.” We just have to pick ourselves up, be truly sorry and start all over again. That process will never end.

The other thing - the real motivation for my journey and the point of this reaction to the book - is the only two commandments Christ ever gave us. Matthew 22: 37-39 "Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbour as yourself.'

What I take from that is that we need to accept life as it is with all its flaws and imperfections and disappointments and hurts and suffering, because I kind of equate God with life. And that we must feel love towards our fellow humans no matter what. We are commanded something impossible, but we are also commanded to keep trying, no matter what.

To me Christianity is outward not inward oriented. How do you manage to keep loving what is out there? I don’t see where prayer of the kind the pilgrim describes helps that, since it seems like a turning away from that imperfect world, which is also turning away from God. I would love to hear what you think about that.

Finally I must stress, I don’t mean any of this as a criticism of you or what you have written. On the contrary, I often sit in church thinking that I am there for the people who sat in those pews before me, not for the church as it is today, which seems full of utter nonsense. If it were not for this group and your writing (and that of a small band of people like Martin S) I would be making no progress at all with my faith. I take a huge amount of comfort and direction from your work and I thank you profoundly for that.