St Seraphim’s Pilgrim Chapel, Little Walsingham, Norfolk, England

I first visited Walsingham in the 1990s, when I was in my mid-twenties. My girlfriend (now my wife) was working as a trainee doctor at a Norfolk hospital, and we found ourselves in the village on one of our expeditions through the local countryside. Back then, very far from being a Christian and generally allergic to religion of all kinds, I didn’t know what to make of the place. It seemed quaint and faintly sinister, like I was in some kind of cultish time warp. I goggled at the icons and the prayer books and the Catholic kitsch. I suppose some people still feel the same if they stumble on the place now. It is strange, the journey that our lives can take us on.

Thirty years on, as I wrote in my first instalment on Walsingham, I could see myself living here quite happily, just as long as I never had to venture beyond the village boundaries into modern England. But I had no particular thoughts of coming back until I was invited last year. It was an invitation which seems to have kicked off all manner of interesting things, including the little Sunday series you are reading now.

The invitation came from Marcus Plested, an English author and scholar who is currently Professor of Greek Patristic and Byzantine Theology at Marquette University in the US. He dropped me a line one day about something I had written, and I recognised his name. I studied Orthodox theology for two years at the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies in Cambridge, which Marcus used to direct and teach on; but it was an online course, so I had the very 2020s experience of being taught by someone I’d never actually met or spoken to. Despite this, Marcus invited me to come and stay with him in Walsingham, where he is currently on sabbatical. It seemed like the kind of invitation that shouldn’t be turned down.

This became clear when I arrived in Walsingham and saw that Marcus and his family were living in a converted railway station:

People living in converted buildings - barns, churches, pubs, railway stations - is not exactly uncommon in modern England. But the former railway station in Walsingham is something entirely unique: it is also an Orthodox Christian chapel and museum, with an intriguing history and an equally intriguing future.

That Marcus and his family are living in this curious building is due to the fact that his wife, Mariamni, is its new manager. Mariamni is an Orthodox iconographer who was born and raised in the Walsingham area. Her father is an Orthodox priest, and she was baptised in this chapel as a child. For the next eight months she will be iconographer-in-residence here. Plans are afoot for gatherings, events and creative projects, all centred around the Orthodox Station.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. The question you are all asking at this point is: Why is a tiny former railway station in Walsingham now an Orthodox chapel and museum, Paul? And if you’re not asking that question, you should be. Keep up.

The railway line to Walsingham used to be known as the ‘pilgrim line’, for obvious reasons. In 1964, though, it was a victim of the Beeching cuts, when 2000 stations and over 5000 miles of track were permanently closed to make room for the emerging car culture. This being Walsingham, though, the shuttered station did not end up as an expensive private home, but as a Christian building which, even by local spiritual standards, is both unique and intriguing.

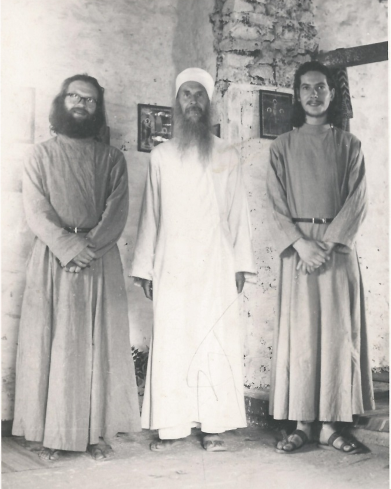

Here is the man primarily responsible:

The man in the middle is a certain Father Lazarus Moore (what a name!) He was an English Christian - initially Anglican, later Orthodox - who, at the time this picture was taken, was running a Christian Ashram in India. Despite being a Christian priest, he is wearing white, not black, in order to fit in with local sensibilities. Fr Lazarus is not the focus of our story this week, though I’d like to find an excuse to write about him in future because his life story is quite the thing. When he first went to India he lived as a hermit in a cave, where he ate roots and berries supplemented by gifts of food from local people, who were used to bringing food to strange bearded sadhus in the wilderness. This sadhu just happened to be a Christian.

But it’s the man on the left with whom our story is concerned. He is another English Orthodox pioneer, Father Mark Meyrick. At the time this picture was taken, Fr Mark was in training for the priesthood. He had been received into the Orthodox Church in 1963, having been mesmerised during an unexpected experience at a Russian cathedral in Paris, and after his time in India he came to Walsingham to take charge of the tiny Orthodox chapel that can still be found in the Anglican shrine that I wrote about two weeks back. Finding it in disrepair though, he and some colleagues began looking around for a better location for a church.

Soon enough, they came across the recently-closed railway station. Fr Mark and his small team had by this time been formed into a missionary brotherhood, named after the Russian wilderness saint Seraphim of Sarov. The Missionary Brotherhood of St Seraphim rented the old station, transported their few goods to it in an old taxi, and got to work transforming it into an Orthodox chapel. The result is the only former British Rail station on the planet that’s topped with an onion dome:

But do you notice the Union Jack bunting on the right of the picture? One of the things I immediately loved about St Seraphim’s when I arrived was how English it all felt. I mean, look at this:

Local preserves, a quiet garden, a little shop, a railway heritage display … it sounds like a village fete. As someone who has experienced his Orthodoxy largely through Romania and Greece, or by reading about saints from Egypt, Russia and other such far-flung places, this combination of Orthodoxy and Englishness warms my cockles. The former Poet Laureate John Betjeman, a High Church Anglican who loved Walsingham, felt the same. Upon seeing the transformed station, he wrote, ‘Now is the Orient come to East Anglia!’

After they had restored the station, Fr Mark and the Brotherhood of St Seraphim built and consecrated a beautiful little chapel within, which is still in use today:

On the wall of the corridor outside is a photograph of Fr Mark in the 1970s, surrounded by the parish that had grown up around the new chapel. Which of these beards are Orthodox, and which are just seventies beards? We may never know:

This is English Orthodoxy in its pioneering days - and it is, quite deliberately, an indigenous strain of the faith. As Marcus writes on his newly-minted Substack from and about St Seraphim’s:

One of the chief concerns of Archimandrite David Meyrick (1930-93), founder of St Seraphim’s in the late 1960s, was to live out a form of Orthodoxy rooted in this land. He and his small community celebrated their services chiefly in English (still quite a rarity at the time) and, even more importantly, set out to explore, venerate, and depict the saints of what the Romans called the alter orbis (‘another world’) of Britain and Ireland. Indeed St Seraphim’s became for some decades a great centre for the hymnography and iconography of the saints of these isles. It was here that many of the troparia and kontakia (Orthodox hymns) for the saints of Britain and Ireland were first composed, here that the icons of many of these saints were first painted. This is, in other words, a form of Orthodoxy very much at home in this corner of the Christian West.

Next to the chapel is a little museum dedicated to Orthodox iconography and various bits and pieces, some of which were used by the St Seraphim Brotherhood when they founded a short-lived monastery nearby in the 1980s:

I got to know this museum well, because it turned out I was sleeping in it. Marcus and Mariamni put me up in a little room off the museum, in an old single bed with a small toilet and a tiny sink in an adjacent room. There were old-fashioned blankets and a complex of old light switches, and if you pressed the wrong one it illuminated the museum instead of the bedroom. Every spare inch of space was crammed with icons, icon-painting equipment or cast-offs from the museum. It was sparse and simple and I loved it. It felt like a monastic cell. In another lifetime, I could have quite happily stayed there as the museum’s live-in anchorite. Maybe they can find someone else for the role. Every museum should have its own hermit-in-residence.

Glass cases aside, though, St Seraphim’s is not a museum; or, at least, not only a museum. All of this history and heritage is fascinating, but though Fr Mark died in the 1990s (by which time he had been tonsured as a monk, and become Fr David instead) the St Seraphim’s Trust, which now owns the building, and Mariamni, who manages it, are keen for it to flourish anew. The little cell I stayed in back in December, for example, is now a working icon studio again. Back in the 1970s, Fr Mark taught himself to paint icons so that he could create images of the British saints, like this one:

Today, Mariamni is hard at work in the same place. Iconography has returned to St Seraphim’s:

As I spent time with Mariamni and Marcus, we got talking about some of the plans they were hatching. One of the first is going to be hatching this May: a weekend-long event at the Orthodox Station on the saints of Britain. I’ll be going along to tell the stories of some of the wild saints, and some old English saints too. I share the view of Fr Mark and his successors at St Seraphim’s: this Orthodox river we have all found ourselves swimming in is not a foreign curiosity, but part of our own heritage in Britain, Ireland and the West in general. It’s not just a historical relic or a subject for travel books: it’s a means of spiritual renewal, if we want it to be.

The British Saints weekend in May is open to all: you can find out more, and book a place, here. Come along if you can. In the meantime, you can find out more about St Seraphim’s on their shiny new website, and you can support them too. You can even sponsor an icon, to help them with their ongoing conservation work, or attend one of Mariamni’s icon workshops. Go to it, readers. Here is an English Orthodox mustard seed, sprouting in the Norfolk hedgerows. Who knows what size the tree will grow to?

This piece is really lovely, Paul, and inspiring.

It makes me... homesick for England, which is not my home country, but a country with whom I have a mysterious feeling of kinship that allowed me to feel a few years ago, in the small shops in Newark, Nottinghamshire, that I had come home, in maybe a way similar to what you talk about above. A revived ? England that has slipped far back out of site, but which is being retrieved through your work, and the work of others, because it has vital things to offer us right now ? Seen from where I am right now, it makes me... a little jealous, a little envious, even, because all this is going on far from where my flesh is, and will remain, and that is difficult for me to accept...

But it is a treat to know it is happening, all the same...

Great piece. The faith Augustine found when he arrived in the 6th century was more “Orthodox” than “Roman,” with an interest in solitude and silence. There is so much in England and Ireland and Wales waiting to be remembered and rediscovered. Not a bad idea these days.