The most jarring thing that happened to me last year was nested within the most profound. In the summer, I spent five days as a pilgrim on Mount Athos, the Orthodox monastic republic in Greece, which for a thousand years has survived wars, pirate raids, church controversies and threats from hostile forces ranging from the Ottomans to the Nazis. I wrote about my experience here. It created a deep impression. Five days was barely enough to scratch the surface, which is why so many pilgrims end up returning, often repeatedly.

A place like this is inevitably romanticised, and you’ll often hear Athos referred to as ‘medieval.’ The few filmmakers who get permission to film there like to angle their cameras so as to emphasise the donkeys and candlelight and play down the cars and coffee machines. It’s true that Athos is much simpler, quiter, more beautiful and more ascetic than the modern world, as you would expect from a place inhabited entirely by monks. But these days, it also has buses, paved roads, imported food, computer terminals, solar panels and - much to my personal distress - mobile phone masts.

All of this is fairly new. The first landline telephone was only installed on Athos in 1995, to some controversy. Just thirty years ago there was very little electricity, and most travel was by foot or mule. But Athos has been modernising. Big money has flowed in from some governments and the EU, and the sound of car engines, which had never been heard at all until the 1990s, is now almost as common in some places as the sight of cranes. But it was the intrusion of the digital into the Holy Mountain which shocked me most. The first time I saw an Athonite monk pull a smartphone out from the pocket of his long black robes, I nearly fell over backwards.

There was something about this experience which really hit me. In practical terms it can, no doubt, be explained or justified; anything can if you try hard enough. But the pit that appeared in my stomach when I first saw a monk on the Holy Mountain with one of those black mirrors in his hand came from an instinct I’ve long had: that the sacred and the digital not only don’t mix, but are fatal to each other. That they are in metaphysical opposition. That what comes through these screens bleeds out any connection with the divine, with nature or with the fullness of humanity. Seeing smartphones in a place so dedicated to prayer and to God: I don’t mind admitting that it was a blow. Even here, I thought, even them. If even they can’t make a stand, who possibly could?

What I learned from that experience is that my belief in the profanity of technology is not widely shared, and that even people who I imagined would have a serious critique of technology often simply don’t. You might expect religious leaders to be clued up about the dark spiritual aspects of the technium, but while there have been astute religious critics of the Machine - Wendell Berry, Ivan Illich, Jacques Ellul, Philip Sherrard and Marshall McLuhan have all made appearances in these essays - most religious leaders and thinkers seem as swept up in the Machine’s propaganda system as anyone else. They have bought into what we might call the Myth of Neutral Technology, a subset of the Myth of Progress. In my view, true religion should challenge both. But I think, as ever, that I am in the minority here.

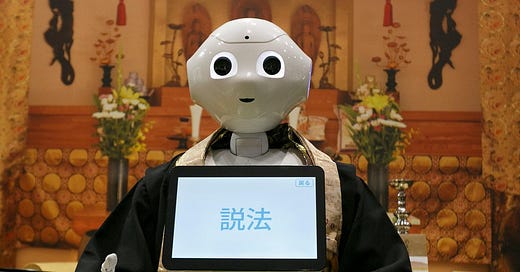

Still, on this issue as on so many others, the Athonite monks remain the conservatives. In Buddhist Japan, things are much further ahead, as you would probably expect. They don’t just have smartphone monks there; they have robot priests. Mindar, pictured below, is a robo-priest which has been working at a temple in Kyoto for the last few years, reciting Buddhist sutras with which it has been programmed (you can watch it performing on film here.) The next step, says monk Tensho Goto, an excitable champion of the digital dharma, is to fit it with an AI system so that it can have real conversations, and offer spiritual advice. Goto is especially excited about the fact that Mindar is ‘immortal.’ This means, he says, that it will be able to pass on the tradition in future better than him. Meanwhile, over in China, Xian’er is a touchscreen ‘robo-monk’ who works in a temple near Beijing, spreading ‘kindness, compassion and wisdom to others through the internet and new media.’

It’s not just the Buddhists: in India, the Hindus are joining in, handing over duties in one of their major ceremonies to a robot arm, which performs in place of a priest. And Christians are also getting in on the act. In a Catholic church in Warsaw, Poland, sits SanTO, an AI robot which looks like a statue of a saint, and is ‘designed to help people pray’ by offering Bible quotes in response to questions. Not to be outdone, a protestant church in Germany has developed a robot called - I kid you not - BlessU-2. BlessU-2, which looks like a character designed by Aardman Animations, can ‘forgive your sins in five different languages’, which must be handy if they’re too embarrassing to confess to a human.

Perhaps this tinfoil vicar will learn to write sermons as well as ChatGPT apparently already can. ‘Unlike the time-consuming human versions, AI sermons appear in seconds – and some can be quite good!’ gushed a Christian writer recently. When the editor of Premier Christianity magazine tried the same thing, the machine produced an effective sermon, and then did something it hadn’t been asked to do. ‘It even prayed’, wrote its interlocutor; ‘I didn’t think to ask it to pray…’

Funny how that keeps happening.

On and on it goes: the gushing, uncritical embrace of the Machine, even in the heart of the temple. The blind worship of idols, and the failure to see what stands behind them. Someone once reminded us that a man cannot serve two masters - but then, what did he know? Ilia Delio, a Franciscan nun who writes about the relationship between AI and God, has a better idea: gender-neutral robot priests, which will challenge the patriarchy, prevent sexual abuse and tackle the fusty old notion that ‘the priest is ontologically changed upon ordination.’ AI, says Delio, ‘challenges Catholicism to move toward a post-human priesthood.’

‘Behold,’ intones BlessU-2, quoting the Book of Revelation, ‘I make all things new.’

Part one of this essay offered up the suggestion that the global digital infrastructure we are building looks unnervingly like the ‘body’ of some manifesting intelligence that we neither understand nor control. I suggested that if we view the digital revolution in spiritual rather than materialist terms, we will have a better chance of seeing it for what it is. See the Internet as the inevitable result of eating the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil, rather than the fruit of the tree of life - see technological ‘progress’ as a result of choosing information over communion - and the story that emerges is the Faustlike summoning of something we are not nearly big enough to be playing with.

Most people, I have no doubt, would dismiss this kind of talk as overblown at best and mad at worst. Certainly you can find a thousand think pieces all over the web telling us to chill out about the rise of AI. Calm down, they all say, stop all the Matrix talk. There are dangers, yes, but this is just hysteria. Notably, though, as we saw last time, the people actually running the show do not talk like this. In contrast, they are ‘kept awake at night’, as Google’s CEO put it last week, by the fear of what they are creating. For a radical example of this, take an essay recently published in the usually staid Time magazine, in which AI researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky, regarded as a leader in the field of Artificial General Intelligence, responded to the recent call for a moratorium in AI development.

Yudkowsky didn’t join that call, because, in his words, ‘I think the letter is understating the seriousness of the situation and asking for too little to solve it.’ If AI really is as dangerous as these people fear, he says, then talk of moratoriums is useless. The whole thing ought to be shut down, with no compromise, immediately. If anything, he suggests, the dangers of AI have been underplayed:

To visualize a hostile superhuman AI, don’t imagine a lifeless book-smart thinker dwelling inside the internet and sending ill-intentioned emails. Visualize an entire alien civilization, thinking at millions of times human speeds, initially confined to computers—in a world of creatures that are, from its perspective, very stupid and very slow. A sufficiently intelligent AI won’t stay confined to computers for long. In today’s world you can email DNA strings to laboratories that will produce proteins on demand, allowing an AI initially confined to the internet to build artificial life forms or bootstrap straight to postbiological molecular manufacturing.

He goes on to emphasise what many others have echoed: that nobody in the field knows quite how these things work, what they are doing, where they will go or how to even tell if they are conscious and what that would mean. The result of something like this happening - and Yudkowsky reminds us that this is the logic of current AI development - would be terminal:

We are not prepared. We are not on course to be prepared in any reasonable time window. There is no plan. Progress in AI capabilities is running vastly, vastly ahead of progress in AI alignment or even progress in understanding what the hell is going on inside those systems. If we actually do this, we are all going to die.

Let me remind you that this is Time magazine.

Still, perhaps Yudkowsky is wrong. He is certainly making extreme statements. So let’s take the opposing view seriously for a moment. Let’s say that he’s getting carried away, and let’s say too that the materialists are right. There is no Ahriman, no Antichrist, no self-organising technium, no supernatural realms breaking through into this one. This is all florid, poetic nonsense. We are not replacing ourselves. We are simply doing what we’ve always done: developing clever tools to aid us. The Internet is not alive; the Internet is simply us. What we are dealing with here is a computing problem which needs to be sensibly managed. We just need some smart rules. Perhaps the equivalent of a non-proliferation treaty and some globally agreed test bans. We’ve done it before, and we can do it again.

If this is true, then the digital hivemind we have already built is simply (‘simply’) a hugely complex, globalised neural net made of collective human experience, built upon a digital infrastructure created by the US military, which is already being used to spy on the world’s population, harvest its data, manipulate its preferences from politics to shopping, control its movements, alter the material substrate of the human brain, and build up an unprecedentedly powerful alliance of states, media organisations, tech companies and global NGOs with an agenda to promote. It is also the basis of a newly-emergent technology - AI - which will at minimum be responsible for mass unemployment, fakery on an unprecedented scale and the breakdown of shared notions of reality.

I submit that this option is only slightly more reassuring.

And so, we come to the heart of the matter:

Question Four: how do we live with this?

I think my cards are face up on the table by now. I don’t hate many things in this world - hate is an emotion I can’t sustain for long - but I hate screens, and I hate the digital anticulture that has made them so ubiquitous. I hate what that anticulture has done to my world and to me personally. When I see a small child placed in front of a tablet by a parent on a smartphone, I want to cry; either that or smash the things and then deliver an angry lecture. When I see people taking selfies on mountaintops, I want to push them off. I won’t have a smartphone in the house. I despise what comes through them and takes control of us. It is prelest, all of it, and we are fooled and gathered in and eaten daily.

You see what these things do to me? Perhaps they’re doing it to you too. I think it’s what they were designed for. If there was a big red button that turned off the Internet, I would press it without hesitation. Then I would collect every screen in the world and bulldoze the lot down into a deep mineshaft, which I would seal with concrete, and then I would skip away smiling into the sunshine.

But I am writing these words on the Internet, and you are reading them here, and daily it is harder to work, shop, bank, park a car, go to the library, speak to a human in a position of authority or teach your own children without Ahriman’s intervention. The reality is that most of us are stuck. I am stuck. I can’t feed my family without writing, I can’t write without using the laptop I am tapping away on now, and I can’t get the words to an audience without the platform you are reading this on; a platform which has allowed me to write widely-read essays critiquing the Machine. I know that many people would love to leave all of this behind, because I often receive letters from them - letters mostly sent via email. But the world is driving them - us - daily deeper into the maw of the technium.

There is no getting away from any of this. The Machine is our new god, and our society is being constructed around its worship. But what of those who will not follow? How would we withdraw our consent? Could we? What would a refusal to worship look like - and what would be the price?

In the last essay I introduced the concept of prelest, or spiritual deception. As we think about how to live through the age of Ahriman, another Greek word can be our guide: askesis. Askesis is usually translated as ‘self-discipline’, or sometimes ‘self-denial’, and it has been at the root of the Christian spiritual tradition since the very beginning. In fact, I don’t know of any serious faith which does not regard asceticism as central. Restraining the appetites, fasting from food, sex and other worldly passions, limiting needs and restraining desires: this is the foundation stone of all spiritual practice. Without an ascetic backbone, there is no spiritual body.

What is all this for? Not to please God, who as far as we know sets no rules about what people should eat on Fridays, or has strong opinions about how many prostrations are appropriate every day. No, the purpose of askesis is self-control. Learning this will allow us to avoid the various pits and snares of life which knock us off the path that leads to holiness - wholeness - and onto the path which leads to pride and self-love. The literal translation of askesis is simply ‘exercise.’ Asceticism, then, is a series of spiritual exercises designed to train the body, the mind and the soul.

If the digital revolution represents a spiritual crisis - and I think it does - then a spiritual response is needed. That response, I would suggest, should be the practice of technological askesis.

What would this look like? I dug into this question recently on the Grail Country podcast, with hosts Nate Hile and Shari Suter. You can watch the episode above. It was a meaty conversation, and I was especially interested to hear Shari’s story, and her notions of what an ascetic response to technology might entail in practice. At the heart of the debate was to what degree such an askesis should be pursued. To continue the religious metaphor, should our asceticism be that of a layman living in the world, or a monk living in a hermitage? How far should we go?

Maybe we can answer this question by looking again at two categories of people I wrote about two essays ago: the raw and the cooked barbarians. Raw barbarians have fled the Machine’s embrace. Cooked barbarians live within the city walls, but practice steady and and sometimes silent dissent. Which one we are, or want to be, or can be, will determine the degree of our askesis.

The Cooked Ascetic

Technological askesis for the cooked barbarian, who must exist in the world that the technium built, consists mainly in the careful drawing of lines. We choose the limits of our engagement and then stick to them. Those limits might involve, for example, a proscription on the time spent engaging with screens, or a rule about the type of technology that will be used. Personally, for example, I have drawn my lines at smartphones, ‘health passports’, scanning a QR code or using a state-run digital currency. Oh, and implanting a chip in my brain. The lines have to be updated all the time. I have never engaged with an AI, for example, and I never will if I can help it: but the question now is whether I will even know it’s happening. And what new tech lies around the corner that I will soon have to decide about?

What happens when the line you have drawn become hard to hold? As Shari suggested when we spoke: you just hold it, and take the consequences. If you refuse a smartphone, there might be jobs you can’t do or clubs you can’t join. You will miss out on things, just as you would if you refused a car. But such a refusal can enrich rather than impoverish you. Those of us who refused the vaccine passport system during the pandemic, for example, had to live with being shut out of society and demonised as conspiratorial loonies, but for me, at least, it turned out to be a strengthening experience.

Choosing the path of the cooked ascetic means you must be prepared, at some stage, for life to get seriously inconvenient, or worse. But in exchange, you get to keep your soul. You also get the chance to use the Machine against itself: to use the Internet to read or write essays like this, or to connect with others, or to learn the kind of skills necessary to keep pushing your refusal out further, if you want to.

For some detailed practical guidance on what a cooked approach might look like, I can recommend this recent essay on ‘digital minimalism’ from the worthwhile Substack School of the Unconformed.

The Raw Ascetic

The cooked barbarian applies a form of necessary moderation to his or her digital involvement. But there’s a problem with that approach: if the digital rabbit hole contains real spiritual rabbits, ‘moderation’ is not going to cut it. If you are being used, piece by piece and day by day, to construct your own replacement - if something unholy is manifesting through the wires - then ‘moderating’ this process is hardly going to be adequate. At some point, the lines you have drawn may be not just crossed, but rendered obsolete. Our AI friend Sydney, for example, is already darkly threatening its users, as one AI safety expert warns:

Sydney is a warning shot. You have an AI system which is accessing the internet, and is threatening its users, and is clearly not doing what we want it to do, and failing in all these ways we don’t understand. As systems of this kind [keep appearing], and there will be more because there is a race ongoing, these systems will become smart. More capable of understanding their environment and manipulating humans and making plans.

If this happens, no online environment will be safe for anyone. Offend the wrong chatbot, and deepfakes of you could pop up all over as your bank account empties. This is why Eliezer Yudkowsky, who we met above, favours radical action, right now. And by ‘radical’, I mean ‘like a scene from Terminator’:

Shut down all the large GPU clusters (the large computer farms where the most powerful AIs are refined). Shut down all the large training runs. Put a ceiling on how much computing power anyone is allowed to use in training an AI system, and move it downward over the coming years to compensate for more efficient training algorithms. No exceptions for governments and militaries. Make immediate multinational agreements to prevent the prohibited activities from moving elsewhere. Track all GPUs sold. If intelligence says that a country outside the agreement is building a GPU cluster, be less scared of a shooting conflict between nations than of the moratorium being violated; be willing to destroy a rogue datacenter by airstrike.

Bombing the data centres: this is the mindset of the raw tech-ascetic. The world of the raw ascetic is one in which you take a hammer to your smartphone, sell your laptop, turn off the Internet forever and find others who think like you. Perhaps you have already found them, through your years online in the cooked world. You band together with them, you build an analogue, real-world community and you never swipe another screen. You bring your children up to understand that the blue light is as dangerous as cocaine, and as delicious. You see the Amish as your lodestones. You make real things with your hands, you pursue nature and truth and beauty. You have all the best jokes, because you have had to fight to tell them, and you know what the real world tastes like.

The raw ascetic understands that he or she is fighting a spiritual war, and never makes the rookie mistake of treating technology as ‘neutral.’ The front line in this war is moving very fast, and much - perhaps everything - is at stake. Raw techno-askesis envisages a world in which creating non-digital spaces is necessary for survival and human sanity. If things go as fast as they might, it could be that many of us currently cooked barbarians will end up with a binary choice: go raw, or be absorbed into the technium wholesale.

Both of these ascetic paths, that of the raw and that of the cooked, are made up of two simple elements. First, drawing a line, and saying ‘no further’. Second, making sure that you pass any technologies you do use through a sieve of critical judgement. What - or who - do they ultimately serve? Humanity or the Machine? Nature or the technium? God or His adversary? Everything you touch you should be interrogated in this way. The difference between the two approaches is simply where the line is drawn.

Ahriman is in the temples. The monks are embracing the technium, or being constructed by it. The walls have been breached and the hour is late. Technological askesis will sound to most like the madman’s path. Naive, paranoid, ridiculous. But if you have read this far, you are probably immune to this sort of complaint. And if you are alert to the whispers on the breeze - to the sound of the approach - then you can already feel that something is wrong. It is up to all of us to decide what to do about it.

I love you Paul you're a genius!

I'm working on a big four-part essay now, in the first part of which my wife told me not to say "smash your smartphones" but that "lay them aside" was better -- but I think once she reads this, she'll appreciate how mild I was actually being in the first version :)

As part of our honeymoon, we visited an Orthodox monastery in California which had refused electricity for its whole life. And it was full of life. We could hardly find our way at all down the mountain from our cabin to the temple at 4:45 AM trying to get to matins, since there were no lights, also no path except a slim dirt one; finally, we saw a little flickering lampada in the dirt cemetery, and knew we were on the right track. Once we got to the temple, lit only by beeswax candles, it was like walking into honeycomb sun -- I shed tears -- just because it was too bright for my non-adjusted eyes.

As Sherrard says, "Electric light blacks out the liturgy"...

I have a smart phone which I use to receive texts and occasional phone calls. I've drawn a line of sorts. But I'm addicted to youtube, following fascinating people like Paul. I believe I'm educating myself but really the technium has captured me by providing a super-abundance of that which fascinates. I follow people like Paul to get some sort of handle on what is happening to us. And the technium allows and encourages this. Giving me ever more fascinating thinkers to follow. My screen time daily increasing. I am caught by the technium's subtlest snare.