Hello everyone, and welcome to November’s monthly salon, which just squeaks in before Advent begins. As ever, this is a space in which readers set the agenda. You can talk about anything you want, and I encourage you to dive in, especially if you’ve not commented before.

Before we get started, I’d like to point you towards a recent conversation I had with Freya India, who writes GIRLS, a Substack aimed at young women and girls navigating life in the Machine. Freya is a sharp commentator on the times - see, for example, her essay on the ‘new religion’ of the self - so I was happy to make the attempt to speak to an audience who are nearer my daughter’s age than mine. It left me with some hope about the moment we’re living in. You can read the original interview over on Freya’s Substack, and I have also pasted the full conversation below.

With that - fire away. If you’d like some prompts, here are a few things which have caught my eye this month:

In advance of the ‘postliberalism’ conference I’ll be attending in Cambridge next month, Nathan Pinkoskie writes in First Things about the ‘actually existing postliberalism’ which has run the show since 1989. He calls it ‘a society in which governmental power, cultural power, and economic power are coordinated to buttress regime security and punish the impure.’

Mary Harrington thinks we are heading into a new reformation in which that regime is now collapsing.

Louise Perry has a powerful article, also in First Things, on the timebomb at the heart of modernity. ‘Could it be’, she asks, ‘that there is a God, and that He does not want us to be modern’? You can probably guess my thoughts on that question.

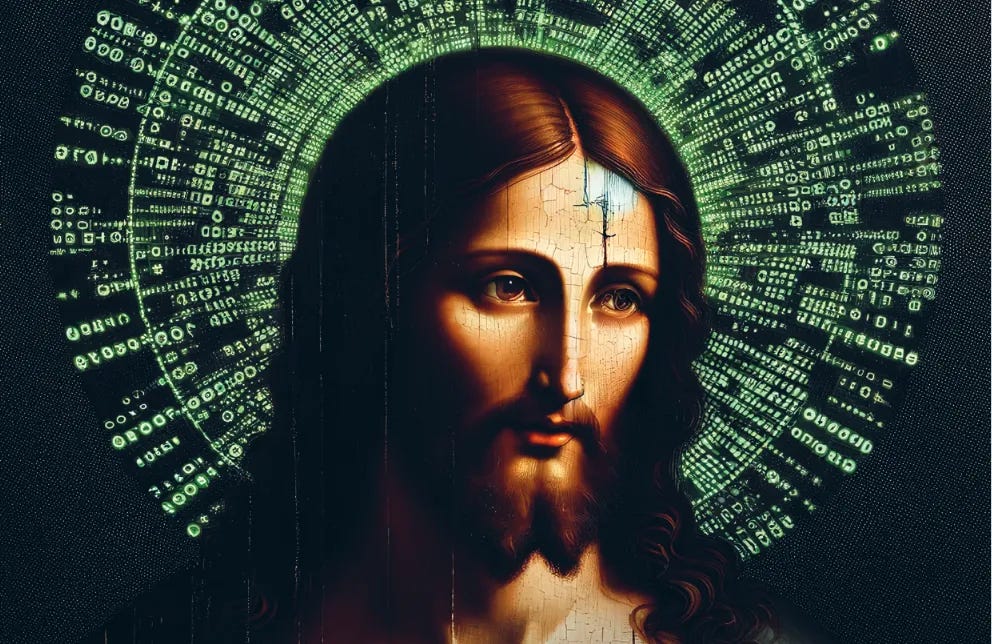

Dominick Baruffi writes about the need for the Church to get serious about the AI revolution and what it means to be human. Immediate support for his argument popped up this week in the form of AI Jesus, a new installation in a church in Switzerland in which techno-Christ can answer all of your questions - though apparently only with religious cliches.

Rejecting The Machine

In conversation with Paul Kingsnorth

Originally published on GIRLS.

Freya India: Paul, there is so much I could ask you. Your essay series on “The Machine” is, in my view, the best articulation of what’s happening to us in the modern world, and where we are headed.

But you are also a father of two, including a teenage daughter. Girls are really struggling right now, as we can see with rising rates of anxiety, depression, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide. Almost everyone I speak to knows a girl or young woman who is falling apart in some way. On my Substack I’ve been trying to work out why, and from my own experience, it’s clear that social media and smartphones are major causes.

In your short story “The Basilisk”, you describe our addiction to phones and the internet as if we are possessed, as if our devices were designed by a demon. You write, “There is a reason they call it ‘the web’...a reason they call it ‘the net’. It is a trap.”

To me social media seems specifically designed to trap girls and young women. These platforms prey on our vulnerabilities. Our faces and bodies are rated and reviewed on Instagram, our popularity publicly ranked on Snapchat. They also draw out our deepest vices. Every typical female bullying tactic—passive-aggression, reputation destruction, social exclusion—is easier online, from the block button to read receipts to full-blown cancel culture campaigns. Basically, if a demon were to design a tool to tempt girls and young women away from “the Enemy”, it would look a lot like Instagram. It is the perfect way to distract, demean, and degrade us. And this demon would, of course, call our degradation “empowering”, our vanity “self-expression”, our sitting alone in our rooms staring at screens “connection”.

All this to ask, how do you resist the Machine while raising a teenage daughter? It’s getting harder to escape. You mentioned in one essay that you won’t have a smartphone in the house because you “despise what comes through them and takes control of us. It is a prelest, all of it, and we are fooled and gathered in and eaten daily.”

How do you protect your family from falling into prelest, and do you still fall prey yourself? Has writing your essay series and forthcoming book affected how you raise your daughter?

Paul Kingsnorth: I don’t quite know how it happened - time seems to move faster as you get older - but I’m now old enough to be your father. My generation - Generation X, as Douglas Coupland, I think, dubbed us - grew up before the Internet, and I’ve come to see this as both a privilege and a curse.

It’s a privilege and a curse for the same reason: that I lived through a time before the web and was able to grow up without it ruining my childhood and teenage years; but now I have to watch it ruining those of my childrens’ generation. I remember a time when you could climb a mountain or walk into a wood and be away from civilisation; there were no smartphones or garmins to tie you into the digital world outside. I remember sitting on trains or in cafes and seeing people talk to each other rather than stare into their little Satanic Rectangles in a silent trance. I remember clubs and festivals when people danced to the music rather than filming it. I remember record shops and bookshops and secret nightclubs before the web killed them off. I remember what small towns were like before Google maps and AirB&B bleached all the mystery and interest out of them. I remember when people still got lost and it sometimes changed them for the better. I remember when you would go somewhere and not know what it was like before you arrived; you couldn’t look up the reviews or the photos online. The world was just more interesting. And a lot less stressful.

Everything you say about what smartphones and social media in particular do to young people, especially girls, is true and I have seen it myself. It breaks my heart every time I see a toddler with a phone or a tablet, already having their mind conditioned for the future they are coming into. I do feel like the Internet is a curse. It tempts us with dopamine hits and social connections and endless information and entertainment, and in return it sucks away our souls, and the souls of our culture. I realise that to some people this might sound hysterical, but I don’t think we’ve seen anything yet. We’re on the cusp of the AI revolution, and very soon our entire perception of reality is going to be challenged at its roots. You quote me as talking about ‘prelest’, which is a Greek word meaning ‘spiritual deception.’ It seems like a good description of what the world of tech is doing to us.

I am just as susceptible to all of this as anyone else. I can get lost down a YouTube rabbithole for hours if I’m not paying attention. Many years ago I had a Twitter account and I noticed that it brought out my most obnoxious and attention-seeking and cruel side. So I made a conscious decision in my life to keep away from these technologies as much as I can, because I know what they will do to me if I don’t. I have no social media accounts, I’ve never had a smartphone, we don’t have a TV in the house and I don’t use satnavs, even though this means I get lost more often. My wife and I made a choice ten years ago to walk away from our urban lives in the UK and experiment with living in the Irish countryside and home-schooling our children. That was at least partly to keep them away from the technological system that was swallowing their peers. My children have never had phones, though they do now have laptops to work on.

I’m proud of the fact that my teenage daughter not only doesn’t have a phone but has become an evangelist for a smartphone-free life to her friends. Interestingly, I don’t think this is because of evangelism from me (being a teenager, that’s more likely to push her in the other direction anyway!) Something is happening in her generation - she’s not too much younger than you - which I see as positive and even exciting. While people like me grew up before the web, her generation have always been surrounded by it. In some ways, that means they are more vulnerable to its pressures, but it also means that they are clearer about its threats. And so there is pushback going on now. Your writing is an example of it.

I think that’s exactly right, there is a pushback happening. I’m hopeful that my generation will be stricter with social media when it comes to our own children, and try hard to preserve their childhood.

It’s interesting that you say social media “sucks away our souls”. I saw a popular, mainstream Substacker describe selfies as “profane” the other day and it struck me. In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt also talks about the “spiritual degradation” caused by social media, which is something I’ve always felt but couldn’t articulate. Degrading is the word. When I scroll through ‘X’ I feel my faith in the world, in other people, and in love, degrading. It’s hard to put into words, but I think of that feeling when you walk into a beautiful, dimly-lit church, where your soul feels a little lighter, where the world feels different—the exact opposite of that feeling is scrolling through TikTok. That’s the only way I can describe it. It’s doing the opposite to your soul.

I’ve also always felt that something about social media degrades our dignity. Everyone talks about feeling insecure or anxious after posting themselves online; for me, the strongest feeling was always shame. There’s an indignity to it, I find—to selfies, status updates, the whole thing. I remember as a teenager every time I posted a selfie on Instagram my heart would pound; it felt wrong, I felt ashamed. Checking how many likes I had felt humiliating. And I don’t think this is unique to me—girls joke about throwing their phone across the room after posting on Instagram, or shaking with anxiety. There’s something in that, I think, worth paying attention to.

I’ve written before about how sharing personal moments online degrades them, almost desecrates them. It reminds me of how my mum has always had this aversion to cutting up family photos—to stick on the wall or put in a scrapbook or something—because she felt it was wrong to cut off someone’s neck or chop off an arm. It’s a feeling like that. Hard to explain rationally, but a sense that something is too special to be treated this way. I just don’t believe we should offer our personal lives up to the market. I don’t post selfies because I don’t want to offer my face to be rated and reviewed. I don’t post my memories because it’s not up to strangers to tell me how valuable they are. If I have a daughter someday I don’t want her to be a product on display. And if I wouldn’t want it for her, why would I want it for myself?

So maybe we do need a little more shame, some stronger cultural norms around these things—where sharing private moments seems strange, where it would be unthinkable for a 12 year-old to have an Instagram account, or shameful to take selfies in sacred places. (Reminds me of another poetic line of yours: “When I see people taking selfies on mountaintops, I want to push them off.”) The other day I watched a group of young women take selfies together in a restaurant the entire evening, barely exchanging a word with one another. While eating, they started editing their photos in silence—one hand editing, the other holding their cutlery. They looked possessed. This is the same generation who say they feel painfully alone. What are we doing?

I wonder what you make of this feeling—that social media doesn’t just harm our mental health, but degrades us spiritually. Do you think that sense of shame is a warning of some kind? And what’s the way out of this? Is there a way to have a presence online while protecting our souls, our dignity, and what we feel to be sacred?

This is very interesting, because I have long felt exactly the same. In fact, I think that this sense of degradation, or profanity, is at the heart of my objection to social media and to the Machine in general. There are a lot of studies I could quote or arguments I could make, and many people have made them much better than I could - Jonathan Haidt, who you mention, is one of the very best at doing this. But at the root of it for me it is just some deep sense of wrongness. Of sacrilege. And that’s hard to justify in the language of our culture.

I sometimes wonder how much of this is cultural. If being English, and being from the pre-Internet generation, just gives me a feeling that what is happening is just bad manners. When did it become appropriate to watch pornography in train carriages? Or to watch a film on your tablet with the volume up in a public place? Or, as you say, to sit in a restaurant curating your online presence on your phone? I realise I’m starting to sound like a grumpy old man, but perhaps we need more grumpy old men, and women, to put things right again.

Speaking of which, you might be too young to remember Mary Whitehouse, the campaigner for ‘decency’ on the TV, who was very well-known from the 1960s to the 1980s. At one point she led a fairly big movement of mostly older, mostly female and mostly Christian campaigners for ‘traditional values’. She was the original critic of the ‘permissive society’ as it was called back in the sixties, and by the time I was growing up she was a running joke amongst the ‘sophisticated’, university-educated, alternative comedy types. Everybody knew she was a fossil and her values were repressive and wrong. Except … these days I find myself basically on her side. She was right about where it was all going, and I suppose that if she could see our pornified present, full of anxiety and anger and broken, fragile young people, she might feel grimly vindicated.

What she represented back then was a culture of limits that was being superseded by a culture of liberation. We all pretended to believe, then as now, that ‘shaming’ people in order to keep society within those limits was bad, and that we should not judge or condemn any behaviour at all, however socially damaging. But no culture in history has ever believed that. And in fact, in the age of ‘cancel culture’ we don’t believe that either. We still shame people for all sorts of things - racism, sexism, homophobia and a host of ‘isms’ real or imagined. What we don’t shame is personal vanity, sexual licence, anti-social behaviour or any expression of sexuality, no matter how niche or damaging. What we have done is to promote personal ‘liberation’ to the exclusion of all other values - and that particular value just happens to be the one which is most easily monetised. The result is a culture in which the pressure to Instagram yourself is both psychologically damaging and highly profitable. The culture is profane and commercial at the same time. They feed off of each other.

We can all feel in some way that this is wrong: that we have let something vital go. The key thing is that, as you say, at some level we seem to feel ashamed of ourselves for the way we are living - and we are deeply unhappy, especially the young. Recently I gave a talk in which I pointed out that the Christian list of the ‘seven deadly sins’ which we used to be told to avoid in order to live a Godly life - lust, gluttony, greed, envy, pride, wrath, sloth - are now the basis of our economy and culture. We don’t avoid them - we actively promote them. This ought to tell us how off track we are. How many people will openly accept that their addiction to TikTok, Instagram etc is a problem, and that they don’t like what it does to them - but then go right on doing it? That’s how we know it’s an addiction. The question is how to break out of it.

I completely agree. It’s hard to break out of the addiction, but I think we have to be honest about what’s actually at stake here. Like our ability to love and be loyal, for example. I think a big fear for young people at the moment is commitment. Commitment to anything, really, but especially to each other.

As you say, the Machine killed mystery, and I think it took romance with it. Now we find our partners by swiping through endless people like products and advertising ourselves like things. When you say Airbnb has “bleached all the mystery” out of small towns, that’s how I feel about social media and falling in love. Romance is dead. You can’t wonder what your crush is up to you anymore because you can just watch their Instagram Story. You can’t wonder where they have been, what music they listen to, what their life is like; it’s all there, listed on their Facebook profile like a product description, their personality packaged into their Instagram grid. And now it’s not just places we review, but people. We leave reviews of one another constantly with our likes, comments and Tinder swipes. Again, profane.

I don’t think this is a small thing. I genuinely believe that what you call the Machine is destroying our ability to love one another. You talk about a time when people wandered in nature and got lost, when people talked to each other on trains instead of looking down, but what I’m most envious of is how people used to fall in love, how they used to stay in love. Many young people today were exposed to online porn before they even had a first kiss. Many of us have never known finding love without swiping and subscription models. We have never known flirting before it became sending DMs or reacting to Snapchat Stories with flame emojis.

Romance is being killed in other ways, too. Our therapeutic culture pathologises love, convincing us that everything is a trauma response, that being dependent on someone is a deficiency. Science and reason remind us that love is nothing more than a chemical reaction. Now a crush on someone is just an attachment issue.

Ultimately I think we are raising a generation full of doubt. The psychologist Erich Fromm talks about “faith” and “doubt” as being character traits, as sort of dispositions of the soul. We are a chronically doubtful generation—of ourselves, of the world, of love, of each other. And we think this feeling of doubt is a reason not to commit to things, whereas really, we are doubtful because we don’t commit.

So, if I’m honest, I’m probably asking you about this because I just like talking about marriage. I love to hear about love, and what it takes—the compromise, the sacrifice, and what comes from that. My generation is starved for love stories. Or commitment stories, you could say. So, what would you say is the value of a committed relationship? Do you also think the Machine has degraded our ability to love? How do we defend marriage and commitment in the age of the Machine, and how important is that?

I think we can’t underestimate the damage that the Machine culture has done to relationships, to love and to sex. You are spot on about this, and you have more experience of it than me. Again, I’m grateful that I was a teenager when we still wrote love letters and made the girls we wanted to impress our own mix tapes on cassette! My first exposure to anything like porn was seeing my friends’ brother’s girlie mags in the shed at the end of his garden when I was about twelve. I didn’t know quite what I was looking at!

We’ve been using words like ‘profane’ and ‘sacrilege’, so let’s dive right into religious vocabulary again and call this what it is: evil. Hardcore pornography, sold to children - or to anyone, actually - is an evil thing. Teaching twelve year old boys to choke women during sex is something my grandparents could not even have conceived of. If the Devil wanted to destroy human love, affection, romance, mystery and family life, he could not have come up with anything better than dating apps, online porn and Instagram feeds. And this is exactly what is happening. Divorce has skyrocketed, the birth rate is plummeting (along with sperm counts), casual sex is valorised - and as a result so many young people long for true love, solid families and just a simple, traditional real human experience of love and longing that has never seemed further away.

Like I say, I see this as an evil thing. I worry for my children, both my son and daughter, because the pressures will come from different angles on both of them, and both will be the subject of dehumanising forces. What can be done? I see the best answer as a determined, voluntary rejection of all of this. Again, I think we can see the seeds of it happening in some people choosing dumbphones over smartphones, and in the kind of critique that you and others are offering. Now I think it needs to go further. There needs to be a movement to reclaim humanity from the Machine, and that includes - maybe should centre upon - reclaiming love, romance and real, human relationships.

If people were to create groups, communities or personal pacts with friends that saw them shut down social media, throw away smartphones, swear off porn and instead begin to meet up - phoneless - to write letters, learn again how to flirt, learn again how to say no, go out without being hampered by tech, experience the world without recording and rating it … it would be quietly revolutionary. It would be a radical rejection of the Machine’s attempts to turn us into objects. But the key would be choosing limits, and cleaving to them. We would need to go back to the understanding that, in fact, our ancestors were not wrong to reject total liberation, were not wrong to have sexual standards, were not wrong to shame those who broke them. Those limits, and that shame, could certainly at their worst be repressive and unjust. But at their best they gave us all a chance to experience real human relationships. Breaking all of the limits has led us into this pornified, commercialised desert of the soul.

We have to get out of the desert. And I think that, despite all this despairing language and the horrors we see around us, there is an opportunity to do it which is genuinely exciting. We are in a pit, and we need to start climbing out. Young people have to take the lead. They need to rise up and reject this culture, and begin creating a new one at the very local level, without waiting for anyones’ permission. If enough people begin trying to create communities with a different kind of life, rejecting the Machine and its tech and its attitudes, things will happen. I don’t mean that you all have to move to rural Ireland. Friends can get together and set new rules any time, starting now. That’s how all change starts. The rejection of the Machine begins in our hearts and then we have to take it into our communities. We need to start telling love stories again. Reclaiming love, and humanity, from the forces which are arraigned against it. That’s the battleground of the age.

I think you may be too humble to recognise this and too British to take it, but there is something unique about your writing. I’m 25 years old, I’m from Essex, I wasn’t raised religious, and I’m not from an academic family. And yet, here I am, reading about Holy Wells every Sunday. What is going on?

Maybe this reflects a wider shift among Gen Z, a search for “re-enchantment”. Something is happening—we are reacting against rationalism and materialism. We are sick of being sold to and selling ourselves. We are grieving a time we never knew.

Even if young people don’t put it into these exact words, something about modern life is clearly making us miserable. The story of progress isn’t panning out. We are reminded how “empowered” we are while many of us feel too anxious to function. We are told we are lucky to be so “connected” while we feel constantly alone and abandoned. We are searching for something more, for stability, for security, to feel we belong to something bigger.

One of my favourite pieces of yours, published in UnHerd, includes a line that always stuck with me: “The Left and corporate capitalism now function like a pincer: one attacks the culture, deconstructing everything from history to ‘heteronormativity’ to national identities; the other moves in to monetise the resulting fragments.” This is exactly what I feel closed in by but couldn’t put into words—a progressive movement burning down everything that once bound us together, while companies commodify all that makes us human. “Capitalism” doesn’t cut it. Neither does progressivism. The Machine does.

Have you noticed this disillusionment among Gen Z, and desire for re-enchantment? What would you say to young people who feel this way? When you feel closed in by both relentless market forces and rapid cultural changes, where do you go? I guess what I’m asking is…do I need to move to rural Ireland?

‘What’s going on?’ might be a good subtitle for my collected life’s work. I have been exploring this sense of dis-enchantment in all my writing for over thirty years, because I think it is absolutely at the heart of the problem of our age. To me, the problems of social media and the like are symptoms of something deeper, and so is the culture war and all the political divisions that are everywhere now. The heart of the matter is that our culture has no meaning to it. It tells us nothing about who we are, what our values should be, what life is for. There is no spiritual heart to it. All our ‘leaders’ can talk about is ‘growth’, and as you note we have a politics which, on both supposed ‘sides’, promotes the interests of what I call the Machine - the technological society which is enveloping us. We are surrounded by endless technological gadgets and consumerist crap because they are all we know how to do. And if the endless promotion of growth-n-progress eats away at all of our traditions, our nations, our cultures, our natural world - well, it’s all a price worth paying for whatever we’re supposedly marching towards. Perhaps the colonisation of Mars.

I think the heart of the matter is that every culture in history has had a spiritual claim at its heart: a notion of connection to God, or in some cases the gods. Even vast empires like that of Rome had a religious core that gave meaning to its strivings. But we have nothing. We are an atheist culture - a Void, as I’ve taken to calling it. We have nothing to say to our young people about what their lives mean. And without that, no amount of information or money or status is going to mean much at all.

So yes, that search for ‘re-enchantment’ is growing fast now. I think it’s going to be the story of the near future in the West. I would not be surprised to see a serious religious revival around the corner. You’re surprised to be reading about holy wells, but I’ve been almost equally surprised to be writing about them! Four years ago, after a very unexpected conversion experience, I found myself a baptised Orthodox Christian. My daughter followed me into the Church soon after. Since I started writing about this I have heard from many, many people with similar stories. Plenty of them are of your generation. If I wanted to look at it positively, I would say that the depths of technological meaninglessness that are now being plumbed, and the misery they are causing, is leading to a kind of spiritual reaction. People think, there must be more to life than this, and then they go looking for it.

Do you need to move to rural Ireland? Well, it would get crowded. I would advise escape in some form, though. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a physical move, though I personally don’t think I could ever cope with living in a city again. But even writing about these issues, as you do, can be a way of escaping being trapped by them. As I said above, getting together with others who think the same, getting rid of technologies that entrap you (start with the smartphone - buy a hammer!), making yourself as economically self-sufficient as you can, swearing off social media and destructive online trends, coming together with others to reject the Machine and its values, reclaiming romance and limits and all the messy beauties of human nature: all of these can be ways of reclaiming your humanity. You never know where this will lead until you set out on the adventure.

Well, I thought I was escaping something when I first started writing online. I thought I was escaping my own head, the craziness of city life in London, the feeling that I didn’t really belong anywhere or to anything. But it turns out I was actually following something the whole time, without realising it. With every word I typed it was as if I was tunnelling my way toward new people, new ideas, and a new life. Through my writing I found my way to thinkers and essays that changed my perspective on myself and the world entirely. So, I guess, if I can be grateful to the Machine for anything, it’s that it led me to your work. I’m sure many others feel the same. Thank you, Paul.

All of my work, my whole life, has been the same kind of tunnelling. Sometimes it isn’t until we write things down that we really understand them, or see where we are going. Writing is a weapon. We have to wield our words at the right enemies. You have identified the enemy. Keep fighting!

This was timely for me. I believe that internet culture has destroyed my 13 year old son's soul. And he doesn't even have a phone or social media accounts. Just occasional use of a tablet provided by his father against my wishes. His favorite YouTuber is especially horrifying. It's just this guy yelling stuff interspersed with flashy graphics that mean nothing. He has 33 million subscribers, and presumably makes millions of dollars by robbing children of their time and degrading their souls. I am with you in calling that evil. My son is unrecognizable from what he was a few years ago, when he loved birds, fishing, and climbing trees. I suppose adolescence would have been rough in any case, but since he started having internet access, it has become a living nightmare; he has no other interests now. The sitcoms I watched as a child in the 80's are like Shakespeare compared to this stuff.

Well before the internet, social media, and AI there was the automobile. In the US especially we built our cities around them such that it's difficult to walk anywhere anymore and even if there is a sidewalk it's at least unpleasant and often dangerous. In the US, at least, this has led to the uglification of our suburban, urban and even many rural areas. While it's fashionable to want to talk about the dangers of AI (and we certainly need to be thinking about these dangers) we often seem to forget that we'd already turned most of our countryside into a wasteland to accommodate the automobile some 70 years ago for the sake of convenience and "freedom" (and this isn't even taking the pollution aspect into account - the aesthetic and psychic damage is bad enough). Now, perhaps part of our problem is that people don't find outside spaces compelling anymore (largely because of what we've done to those spaces) and thus it doesn't seem too surprising that people want to retreat into a more disembodied existence. And then comes along television and then the internet and then social media and now AI and here we are. Humans are more than willing to sacrifice well being for convenience. I think a lot of us want to be able to resist the allure of convenience, but it's very difficult - and the great majority of people don't seem to be inclined to even try to resist. How can this change?

AI is just the latest technology offering convenience in a long line of such technologies. Of course, it has the possibility of surpassing all of the previous ones in that it could become self-replicating and self-improving. We haven't done very well in resisting the convenient technologies of the past and I guess I'm not very optimistic that we'll be able to resist going forward.

This latest article from LM Sacasas seems relevant: The Enclosure of the Human Psyche https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/p/the-enclosure-of-the-human-psyche