Binham Priory, Norfolk, England

We’re still in the flatlands of Norfolk this week, but we are leaving Walsingham behind and heading out into the countryside. In our first couple of instalments here, we explored Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, and the subsequent ransacking of religious sites around the country. We’ve looked at the destruction of the ‘holy house’ and its associated shrine - but how about those monasteries? What kind of state did they end up in after Henry and Cromwell’s men went to work?

Let’s go and find out.

As you’ll know if you’ve been reading me for a while, I’m something of a fan of monasteries. I admire the commitment and self-sacrifice of monastics, and I find much of their way of life deeply appealing. The simplicity, the focus on God, the lack of trivia, the stripping away of all the unnecessary things. There is something monastic about me, I think. On the other hand, there is quite a lot of me that is very unmonastic: for example, the parts that don’t like getting up early, but do like complaining about authority, making rude jokes and eating too many Maltesers. I think I would make a good monk, in the same way that I think I would make a good martyr: I can visualise it easily, but that doesn’t mean, when the chips were down, that I’d be able to actually do it.

Anyway, as I say, I’m a fan of monasteries, and I hold Fat Henry responsible for their widespread destruction across England. Unfortunately, with the best will in the world, it is not always possible to report that the monasteries he destroyed were supremely holy places. In fact, the complaints of Reformers right across Europe - complaints about over-wealthy monastic houses, lazy and corrupt monks and abbots, and a general atmosphere of decadence and unholiness - were not always entirely unfounded. Sometimes, in fact, the monasteries had become so dodgy that they were practically offering King Hal a gold-plated excuse to close them down and cart away all their cash to the royal treasury .

And so we come to Binham Priory.

Binham was founded in 1091, exactly thirty years after Richeldis de Faverches had her vision of the Virgin Mary in nearby Walsingham. Over the next couple of centuries it became one of the biggest and most impressive monasteries in Norfolk. Architecture nerds remain excited by it, as it contains the earliest example of bar tracery windows in England. What does this mean? Well, it means that the architectural style known as Gothic was beginning to develop. Previously, Norman (or ‘Romanesque’) churches had had small windows like this. Bar tracery allowed the construction of bigger windows, which let in more light, like this.

Unfortunately, the once-majestic early Gothic windows of Binham started collapsing in the 1900s, so the Victorians walled them in with brick:

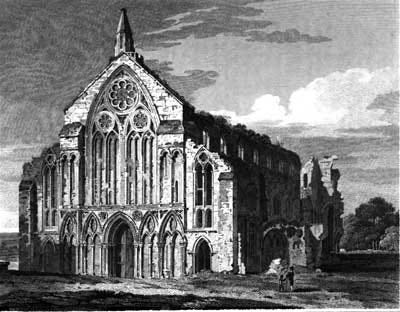

You can see what they would have looked like before in this old engraving:

Still, the magnificent doorway on the west front of the nave is still going strong:

All in all, in fact, the heart of the old priory is in remarkably good condition. Look at these windows, and the roof. And are those medieval drainpipes?

Well, no. You see, while the monastery as a whole was dissolved in the sixteenth century, the heart of the old priory was retained, and became the parish church. It is still in use today by the local Anglicans. So while much of the former monastery now looks like a blasted ruin, the old nave stands tall above it:

Inside, it looks like this:

What has happened here is what happened across England during the Reformation: an old Catholic building was repurposed as an Anglican church. In the process, anything associated with the idolatries and superstitions of ‘Popery’ - statues, rood screens, paintings, frescoes, crucifixes, holy wells and the like - were either smashed, removed or painted over. Walk into an English parish church today and the building will typically be whitewashed and full of dark wooden pews. It will be simple and clean-lined. Before the Reformation, however, these buildings would have looked more like an Orthodox church in Eastern Europe today: painted in many colours, filled with icons and statues, dotted with reliquaries, rood lofts and even the cells of anchorites - of which we will discover more in coming weeks, as we continue to wander across England.

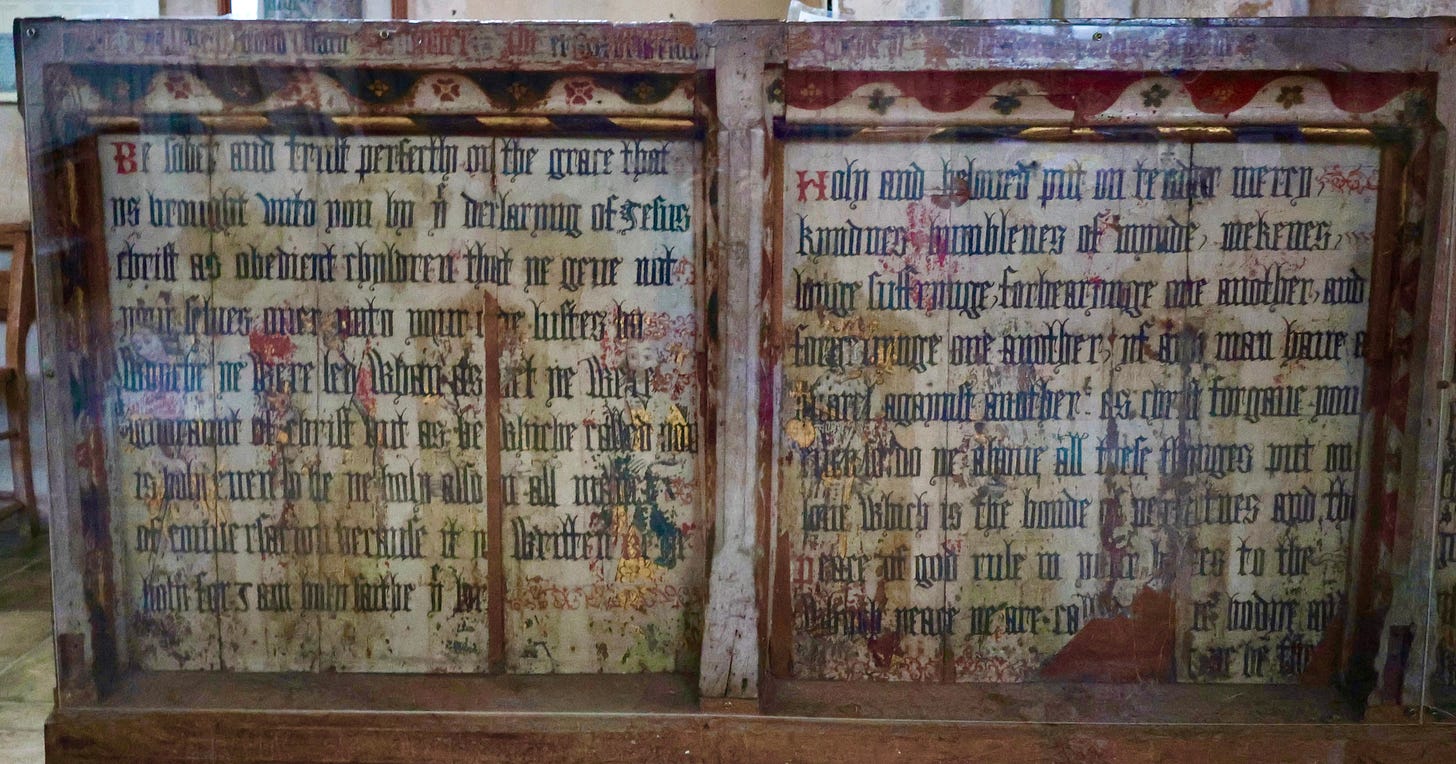

Binham has a famous example of such Reformation-era remodelling. Below is what was previously the rood screen (‘rood’ is an Anglo-Saxon word for ‘cross’; it gives its name to a famous Old English poem) separating the nave from the chancel and sanctuary. In medieval times, it was painted with icons of saints. After the Reformation, it was whitewashed and covered instead with Bible verses. Sola scriptura, and all that:

Look closely though, and you can see the saints starting to re-emerge from under the fading paintwork. I’ll leave it to you to decide on your own choice of historical symbolism for this occurrence:

Somehow, the Reformers missed the opportunity to trash Binham’s impressive font. It’s known, apparently, as a ‘seven sacraments font’, because each side contains a carving of one of the seven sacraments of the Catholic Church. There are about thirty surviving examples scattered across East Anglia. Maybe even the Protestants had a soft spot for such magnificent work:

But didn’t I hint at some dark monastic goings-on? Didn’t I promise mad monks and alchemists? And haven’t I delivered lectures about windows and rood screens instead? It’s a good job none of you are paying for this.

So: it turns out that Binham’s beautiful architecture did not necessarily translate into beautiful Christian living. In fact, according to English Heritage, which looks after the place, ‘its history is one of almost continuous scandal.’ Having been founded by a nephew of William the Conqueror (himself a one-man scandal), Binham started life with just eight monks, and despite its huge size it apparently never housed more than fourteen.

Its Priors, though, were the main source of its problems. They frequently squabbled with their superiors at the nearby Abbey in St Albans. In 1212, the ongoing squabbles developed into a literal battle, when the Abbot of St Albans sacked the Prior of Binham for his misbehaviour. This did not go down well with Robert Fitzwalter, local Earl, friend of the Prior and enemy of the unpopular King John (Fitzwalter was one of the barons who later forced Magna Carta onto the reluctant King.)

Fitzwalter produced a forged deed of patronage which claimed that Binham’s Prior could not be removed without his consent, and then proceeded to lay siege to the Priory. The monks, unable to escape, were forced to drink water from the drain-pipes to survive. When King John heard about the siege, he apparently swore an epic medieval oath: 'By God's feet! Either I or Fitzwalter must be King of England!' Then he sent a group of soldiers to relieve the Priory.

By God’s feet!, I think, is a curse I am going to try and use in the future.

A century or so later another Prior, William de Somerton, flogged off much of Binham’s wealth, including ‘two chalices, six copes, three chasubles, seven gold rings, silk cloths, silver cups and spoons and the silver cup and crown in which the Host was suspended before the altar’, using the proceeds to fund his experiments in alchemy. When the Abbot of St Albans visited Binham to find out what was going on, de Somerton and his wealthy local friends refused to let him in, and Edward I was forced to intervene, arresting de Somerton and all the monks.

A century later, another Prior, William Dyxwell, was deposed because he ‘wandered about from place to place like a vagabond’, though he was later reinstated for life. Perhaps he was a Fool for Christ, or perhaps he was just a fool. Either way, it’s not surprising to hear that, when Henry VIII’s men wanted to dissolve the Priory in 1539, they were not short of excuses for doing so.

There’s one last story that is worth sharing about Binham: it has a ghost, as every ruined monastery should. In fact, it has two. One of them is, of course, the ghost of a monk. It is said to emerge from a secret tunnel connecting Binham with the shrine at Walsingham. Nobody seems to know where this tunnel is today - but Binham’s second ghost is evidence that somebody once did.

Once upon a time, the story goes, a local man named Jimmy Griggs discovered the tunnel and went in to explore it, accompanied by his dog, Trap. Jimmy was a fiddler, and as he walked along the tunnel he played his fiddle so that his mates above ground could tell where he was. Then, suddenly, the fiddle stopped - and Jimmy was never heard from again.

They say that Trap escaped, though. They say, too, that Jimmy’s fiddle can still be heard some nights, when the full moon is high upon the ruins of Binham …

Echoing the comment below, I wonder if Henry VIII was the beginning of the "welfare state". Up till then the church had collected tithes or taxes and used them - or was supposed to use them - for education, health care and the relief of the poor. Secular governments - kings - were more about defence of the realm/conquest. There is no perfect system. There never can be. As Paul has written elsewhere, we are all fallen creatures. But a state in which education, health care and the relief of the poor are underpinned by shared spirituality seems to me a much better way of organising things.

Somewhere I heard that with the dissolution of the monasteries (however corrupt some of them might have been) the very fabric of communities was rent apart. I can well imagine this. I live near a monastery and even today, monasteries provide purpose, spiritual meaning, and succour to local communities. As of old, monasteries today can be corrupt, but the heart of them is above that. The loss of so many holy places which were also a practical help to their communities cannot be under-estimated. I wonder if this was the start point for the gradual loss of Christian belief in Britain. Imagine how it might have panned out had those monasteries thrived over the following centuries.