St Flannan’s Well, Killaloe, County Clare

Last week we were on a quiet island in the middle of Lough Derg. This week we’re in a slightly noisier, but still small, town at the south end of the lough. Killaloe is a nice little place, with a beautiful stone bridge across the river and a good number of visitors who come to fish and hire boats in the summer. And like virtually every other old settlement in Ireland, it also has its own holy history.

Killaloe is especially associated with the seventh century saint Flannan, a wandering founder of churches as far afield as Inishbofin and the Hebrides. He was busy as well here in Killaloe, where the twelfth century cathedral - now Anglican - is named after him:

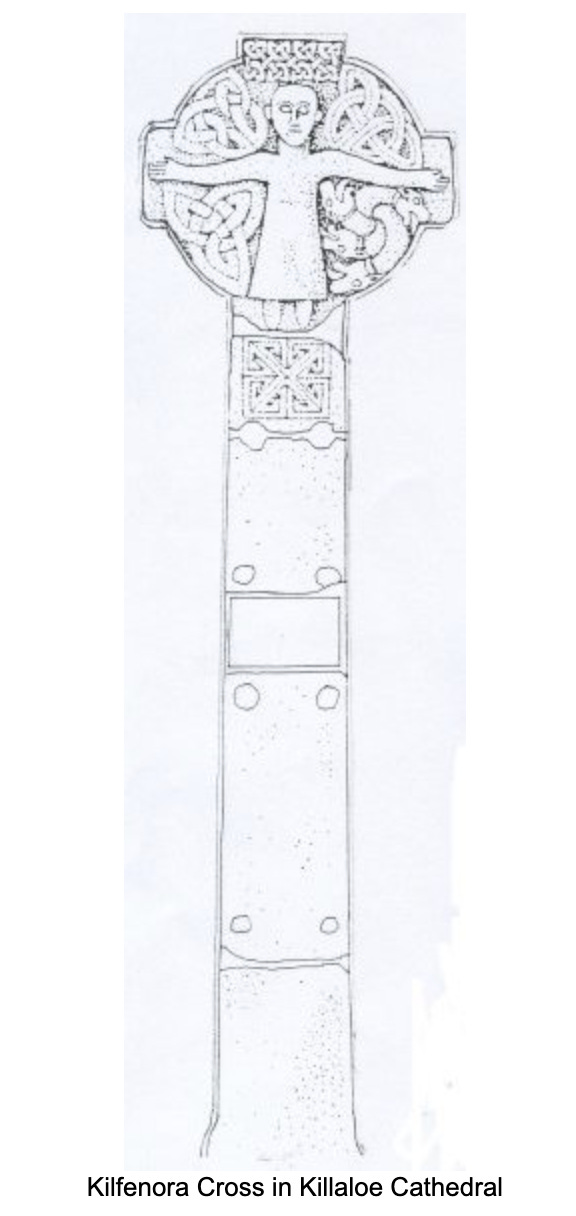

The cathedral may be old, but that little stone building on the left is even older. It’s an oratory church, which reputedly dates from St Flannan’s time, and which may even have been built by the saint. Inside the cathedral is other evidence of the ancient nature of this early Christian site, including a twelfth-century stone high cross with a design which is beautifully primitive, in the best way:

Even older than the cross, and virtually unique in Ireland (there is apparently just one other extant example) is a standing stone which features writing in both Irish Ogham script and Nordic runes. Perhaps it was the work of a particularly multicultural Viking:

Both of these ancient stones are currently on display inside the cathedral, which given the Irish weather is probably prudent. Once on display here also, until Henry VIII’s mobs got hold of them, were St Flannan’s relics.

But Paul, I hear you exclaim, knowledgeably, a Christian site this old and complex must surely have a holy well associated with it! To which I reply: yes, indeed it does. Only it is not where you might expect to find it.

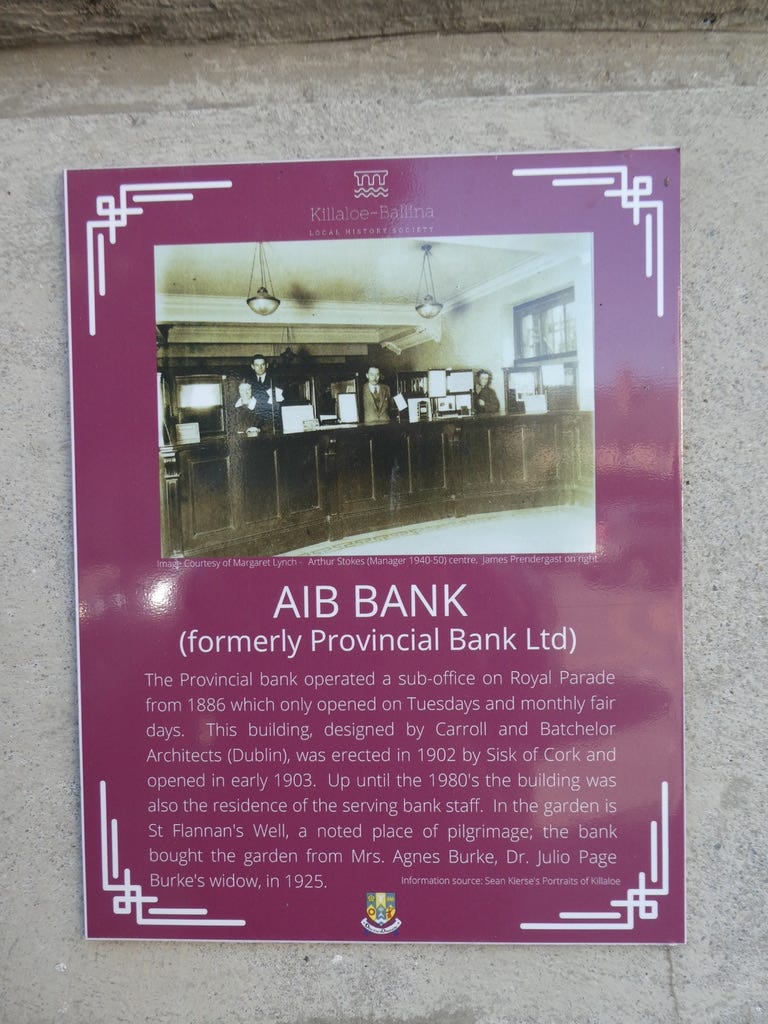

In fact, you will find it here:

This is the local branch of AIB bank, on the opposite side of the road from the cathedral complex. St Flannan’s Holy Well, Killaloe, is the only well in the country which is situated in the back garden of a bank:

My wife and I wandered into the bank on a warm summer day last year in the hope of getting to see the well. I wasn’t very hopeful. I’d read that the garden is closed to visitors, though it is sometimes opened to pilgrims on the saint’s patron day. Still, we waited in line to speak to the bank clerk just in case.

Can I help you? said the smiley lady, perhaps anticipating a mortgage- or loan-based inquiry.

Er, I said, well, I’m a writer, and I’m writing a book about holy wells, and I was wondering if it might be possible to have a look at the one in your garden?

Strictly speaking this was a white lie, but I’m writing some stuff on the Internet just never sounds as good. I’m writing a book can open doors sometimes, if you’re lucky. It’s one of the perks of being a writer.

This turned out to be one of those times. The lady with the keys just happened to be on the premises, and the young bank clerk we’d spoken to was keen to come along too. I’ve never seen the well, she said, so your visit is my excuse.

They opened the door to the back garden, and out we went. Through the long grass, at the back of the little suburban plot, was a wonderful pile of ancient stones. Incongruous among the neat flower beds and the backs of terraced houses which stood sentinel around it, the water flowed out of a fern-hung, underworld opening that would have been a better fit in the wild mountains of the west:

But there was something else too, which the bank lady had to point out before I noticed it. Have you seen our Sheela na gig? she asked. I hadn’t - but now that she pointed it out I could see it, nestled silently among the stones at the front of the well:

It’s hard to see what's going on here unless you know what to look for, but what we’re looking at here is another ancient stone, perhaps of the same kind of vintage as that high cross. A Sheela na gig is a strange thing indeed: a grotesque carving of a woman opening her vulva for all the world to see. In their undamaged state, they look like this:

These figures are found in various Western European nations, and always in Christian sites, despite their very non-Christian appearance. Ireland has the largest number of surviving examples of any country, at 124. What are they? As with the equally intriguing figure of the green man - rare in Ireland but common in England - their obscure origin and presence in Christian sacred places has led to a wealth of speculation. Were they charms to ward off evil? Warnings about the sinful consequences of female lust? Secret remnants of an ancient fertility goddess religion snuck into Christian places? You name it, there’s a theory for it.

All of which means that, in the end, we don’t know. Like so much about the wells, there’s a mystery at its heart. What we do know is that it is a very unusual bank branch which can boast an ancient well and a Sheela na gig in the back garden. Only in Ireland. Long may it continue.

So, until the ‘80s the bank staff used to live in the bank. I wonder if they ever felt like they were stepping into Narnia as they opened that back door with its remarkable holy well and mysterious Sheela na gig. These stories are really interesting ….wardrobe doors in themselves, ushering us into Narniaic lands…

How unexpected and awesome!

I discovered the Sheela-an-gig image as a teenager and loved it….but eventually moved on and didn’t pay it much mind until I was pregnant with my first daughter and reading Ina May Gaskin in preparation for giving birth. Ina May suggests that it is not obvious to women in the modern era what our bodies can do, but images like the Sheela-na-gig remind us how big we can get (I’m paraphrasing from memory). I found this a confidence boost.

Another piece of wise advice from Ina May is to not try to think through everything with your brain and trust what your body knows. Good advice for birth but also in general. It is good to be in your body, experiencing granular, complex, even contradictory reality.