My friend Martin Shaw, a mythologist and storyteller, likes to say that ‘civilisation is three days deep’. By this he means that, once you walk away, turn off, tune out or otherwise unplug from the matrix, it takes three days to slough off the accreted junk that the world has filled your mind with, before you can begin to see the shape of reality again - or simply to experience the world around you with genuine human attention.

I’ve been away in the mountains for a week, and having just (reluctantly) returned, I’ve found this to be as true as it has proven to be many times before. The immense falsity of the Machine is revealed the longer you spend away from it: even a single week begins to show it up for what it is. But this does make the re-immersion tricky. So please forgive me as I work my way steadily towards my next essay, which will be with you in the next few days. I’ve been immersing myself in Julian Jaynes, Simon Schama, Robespierre and Ian McGilchrist for the purpose, and now I’m beginning the task of pulling it all together without getting the bends.

In the meantime, I thought I might offer up some reading suggestions from elsewhere in the expanding ecosystem that is Substack. There are some interesting people writing here, united by little more than the fact that they seem to find it more convivial, freeing or perhaps just relieving to say what they want and need to, in a space which encourages rather than limits freedom of expression and thought. Let’s hope it lasts.

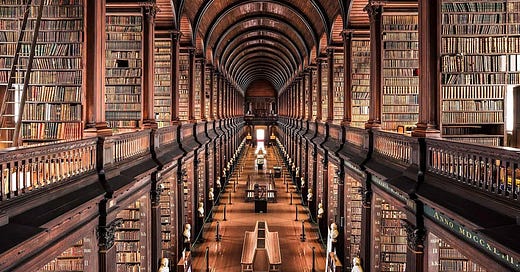

If it doesn’t, it might be for the simple reason that we are forgetting how to actually read - at least according to Angela Nagle, whose newsletter I highly recommend. In this recent essay, she connects the decline in Protestantism to the rise of the Internet and the ongoing collapse of literate culture. What will be the future, she asks, for nerds like me - and perhaps many of you - in a coming world in which books are not just undervalued but at a fundamental level barely even comprehended?

The … possibility is that real reading and the kinds of thinking and being it produces will leave the dwindling reading population hopelessly out of step with the entire value system and way of life of the broader culture, and even unable to communicate effectively using the visual narrative sensibility that is required to influence and gain power in society.

Some of us are starting to feel like we’re here already - though this could just be middle age.

Meanwhile, in Bari Weiss’s newsletter Common Sense, a go-to source for news of America’s rolling Woke Jihad, Abigail Shrier writes an unsettling article about a more immediate threat to literature: its banning. Reading Fahrenheit 451 as a teenager, I remember shuddering at the thought of a society where books could be banned, and feeling grateful not to live in one. Now I find myself reading the (increasingly common) story of an author whose book challenging one of the fleet of new orthodoxies - in this case the ‘transitioning’ of children - is being censored by Big Tech, and its author abused in a campaign of disturbing vitriol.

How did we get here, and so quickly? We’re still all trying to answer that question, but especially piquant to me are Shrier’s accounts of the emails she receives from people who claim to support her but who refuse to do anything to demonstrate it. They’ll clap her on the back for taking the flack, but they won’t take any of it with her. Having experienced a similar situation myself in the past, though on a thankfully smaller scale, I came to the same conclusion as Shrier: it is precisely this kind of ‘supportive’ silence that allows tyranny to take root. Her advice is worth us all brooding on:

It is easy to justify our silence. We tell ourselves that we are protecting our families by remaining quiet, and in the short-term we may be. But we are also handing our children over to a culture in which freedom of conscience and expression are drowned out. We are teaching our children that truth shouldn’t be our primary concern — or at least, that truth is negotiable or subordinate to being agreeable. They are learning that it is more important to remain acceptable to the powerful than to be truly free …

Angela Nagle describes the dominant ‘NGO-media-academic-professional activist class’ that creates and sanctions this conformist atmosphere as a ‘clerisy’. She describes the age of populism and culture war as:

…a struggle between the clerisy - a vast secular moral teaching class created in the 20th century who accrue power, set the terms of moral virtue and prestige and parasite existing wealth through producing and maintaining ideology - and those who found themselves outside the clerisy, subject to its punitive rules without gaining any benefits from its parasitic existence.

N. S. Lyons’ Substack series The Upheaval digs deeper into this ongoing ruction. The latest essay, Four Big Questions for the Counter-Revolution, takes cultural disintegration for granted, but asks what it really signifies, where its roots lie and where those of us who are not amongst the clerisy might find answers to its emergence.

If you want another angle on the cultural earthquake - specifically, the viewpoint of a gay, left wing, Jung-quoting American druid living in Belgium - you might try Rhyd Wildermuth’s series From The Forests of Arduinna. Rhyd is one of those writers I read at least partly because I know I am going to argue with half of what he says and agree with the other half, but I’m never quite sure which is going to be which. His recent essay on mass hysteria and possession as an explanation for the current landscape is well worth a look.

Finally, let me tip a hat to two other writers on here that I appreciate engaging with. The Convivial Society is an ongoing series from L. M. Sacasas exploring technology and our relationship with with it in the age of the Machine, influenced in particular by Ivan Illich and Jacques Ellul, two thinkers I’ll be exploring later down the line. And if you want to leaven your Marxist druid with the perspective of an Anglican ‘young fogey’, Further Up from Esther O’Reilly is worth exploring too.

I’d say that’s enough to be going on with. If any of you have suggestions to offer in turn, I’ll be glad to hear them. In the meantime, I’ll get back to my essay. Watch this space.

The growing dislike of books seems to accompany a growing dislike of truth itself. The idea that the world is plastic and we can mould it to suit 'our truth' seems to grow as we 'harden our hearts' and make ourselves the opposite of the 'clay' in the potter's hand.

If we refuse to be the clay (as the 'uberman' does), then other things (and people) have to be marred beyond recognition, because God has not made the world this way; he has actually made it so that WE can be shaped by IT).

I'm seeing things as an arc along the same line which actually turns full circle.

As Jesus is the alpha and omega, so hatred of Him has an alpha and omega - full circle.

I'm thinking of Romans as a universal truth:"...just as they did not think it worthwhile to retain the knowledge of God, so God gave them over to.... do what ought not to be done..."

I'm thinking of how the circle may be nearing completion in Canada, which is possibly at the far end of 'woke' countries, with the detention of a pastor for organising outdoor, socially distanced meetings in order, to sing, pray and read, with 25 or so other people, since they were unable to do so indoors. Unable to promise he would not do so again, he has been refused bail and so now languishes in jail.

So the rebellion against the 'truth' of the world eventually exposes itself in hatred for all talk or celebration of the maker of that world. To rebel against reality is to rebel against God.

'crucify him' becomes 'let it all burn'

So grateful for these links to many new to me and intriguing writers. Your essays are always eye openers and fantastic that you are sharing other voices as well 🙏🏼🧡🙏🏼