Intermission: From The Library

Some recommended reading for the winter

If you are anything like me, you can sense on the breeze that things are accelerating out there. ‘Events, my dear boy, events’, as the last old-school British Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, once put it, are moving in such a way as to force many hands.

I’ve been saying for a year or two now that we are living in apocalyptic times, and I mean that literally. The Greek word Apokalypsis means unveiling - or, of course, revelation. In Apocalyptic times, things are revealed which were previously hidden. The world is shown to be a different shape to the one you thought you were living in. This is rarely comfortable. If you pay attention, it may change your life. We each have to decide what to do with what is revealed to us.

The covid pandemic is an apocalyptic agent in this sense. As it rips through the body politic, the culture, the world, it reveals what is weak, where the breaks are, what is truth and what are lies. Those who would tell the lies find it harder by the day to do so without truth leaking out around the edges. Systems that we all knew, somehow, didn’t work the way they should, are revealed in all their flawed construction. Politics is accelerated. Tribalism and suspicion come into full flower. Our limits are revealed. Our trembling stories crack and cannot be put back together. And through it all, some higher spirit rushes.

All of this is in some way a blessing, even though it mostly feels like a curse. It is most certainly a spiritual lesson for us. We just have to understand what we are being taught. And we have to understand that spiritual lessons always come with a price attached. Insight is never free. Nothing is going back to its former shape. There is more revelation to come. We need it, though we don’t want it.

I’m building up to writing soon about this pandemic, what it means and where the truth might lie, as far as it is possible to know. What at first I thought - perhaps we all thought - was going to be a six-month inconvenience has become an endless, rolling instrument of revelation. It has exposed the Machine to the light. I want to get my ducks in a row before I add to the cacophany of noise on this subject; more soon.

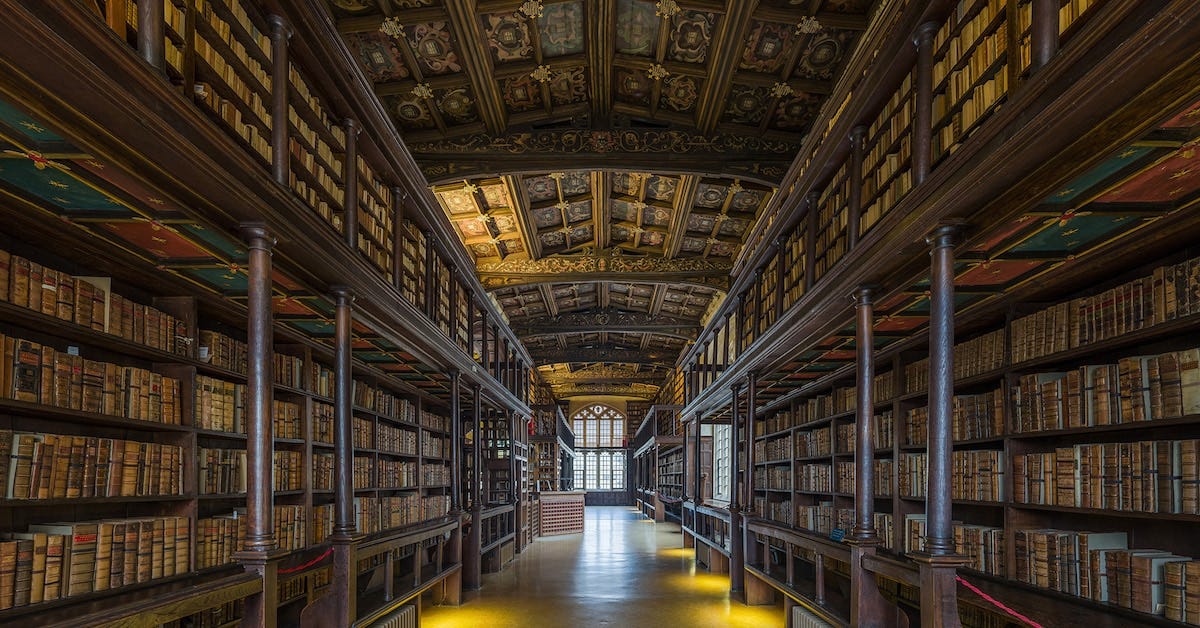

In the meantime, I want to recommend some books that I’ve recently enjoyed. That’s right - real, physical, musty, tactile, life-affirming books! Books - the right books, anyway - are an antidote to the Machine, and they will outlast it. Books beat screens every time, and I will die before I ever say otherwise. These are a few I’ve recently found to be worth reading, which tackle the same themes as my essays and which deserve to be better known:

Hyperreality is a new book by Dutch journalist Frank Mulder, which investigates the construction of the metaverse. It’s a fairly slim book, which draws on René Girard and Jacques Ellul, who I’ve written about here recently, to examine how our technology is controlling us daily. Mulder is a Christian, and his conclusion - like mine - is that the rise of the Machine is a spiritual challenge; an attack on what it means to be human. Any resistance to the Machine must thus be spiritual too.

A few years older is Lawrence Millman’s book At The End of the World. I met Lawrence a few years back in the US, where he took me on a sightseeing trip to Thoreau’s grave. If this is a writer’s idea of a good day out, you know they’re worth reading. This book does something I’ve not seen before: it combines true crime - the story of a historic murder in a remote Inuit community - with a caustic meditation on the darkness of modern technology. Lawrence is both a neo-Luddite and an expert in all things Arctic, and both strands knit together into a working story. It’s splendidly written, and funny, and it gets to the heart of the thing.

Another timely read is John Rember’s new essay collection A Hundred Little Pieces on the End of the World. Rember is also funny; but rarer than that, he is often wise. I published some of these essays back when I was running the Dark Mountain Project, and collected together they work as a kind of road trip with a trusted guide through the symbols of the crumbling age: CO2 emissions, microplastics, ski trips, psychotherapy, Stephen Jay Gould, Foucalt, smartphones, millennial anxiety, survivalism and college loans.

Finally, a plug for a new reissue of a very old book, for which I recently wrote the introduction. Everett Ruess: a Vagabond for Beauty is a collection of the diaries of a young wanderer who went missing in the deserts of the American West in the 1930s and was never heard from again. It’s a classically Romantic tale of wandering in the wilds while they were still undefiled, and it ascends towards the end into a particular kind of profundity.

In a few weeks, I will gird my loins and recommend some screen reading too. There are more and more writers and investigators popping up out there with the right questions on hand. This alone should give us good cheer

Something that I read over the past month was the Deed of Paksenarrion by Elizabeth Moon, one of the best fantasy pieces I've ever stumbled across and it has a message that I think is extremely apt for this substack. Because Paksenarrion journeys as a paladin in complete dedication to the 'High Lord' of her world, but the parallel to God is easy to see. She fights a much needed conflict against nihilism, evil, and a bunch of other things and through redemption wins out in the end.

Right now, I'm reading 'Life Is A Miracle' by Wendell Berry (after repetead mention of his name by Paul). It's a welcome antidote to another book I read recently by Carl Sagan, called 'The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark'. Sagan is a really nice person, and I felt I owed it to him to read the book. I had bought it years ago after watching the Cosmos series with my homeschooling daughter.

It was a hard read, partly because it's repetitive (science is the best thing we have, despite its flaws, and people are stupid) and a lot is about the misguided belief in UFOs. But I've also moved past this phase of being in awe of science and technology. In 'Life Is A Miracle', Wendell Berry does me the great service of putting my visceral reaction when reading Sagan's book, into words.

And there's this wonderful quote in the middle of the book that - to me- explains much of what is going on with the pandemic, both at the top and on the bottom:

"The next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines."

I felt like I'd read it before, maybe it's earlier in the book, or maybe Paul or someone else had already mentioned it somewhere. Either way, I might have to get that tattooed somewhere so I never forget it. ;-)